Are Judaism and Christianity as Violent as Islam?

by Raymond

Ibrahim

Middle East Quarterly

Summer 2009, pp. 3-12

http://www.meforum.org/2159/are-judaism-and-christianity-as-violent-as-islam

Medieval times:

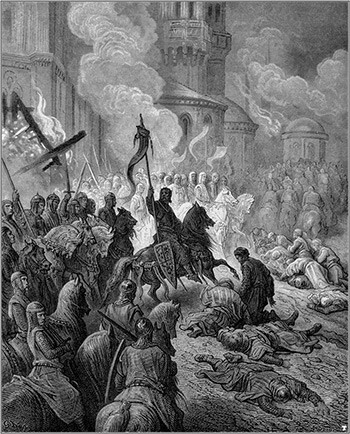

The Crusades were violent and led to atrocities by the modern

world's standards under the banner of the cross and in the name of

Christianity. But the Crusades were a counterattack on Islam. Muslim

invasions and atrocities against Christians were on the rise in the

decades before the launch of the Crusades in

1096. |

"There is far

more violence in the Bible than in the Qur'an; the idea that Islam imposed

itself by the sword is a Western fiction, fabricated during the time of

the Crusades when, in fact, it was Western Christians who were fighting

brutal holy wars against Islam."[1] So

announces former nun and self-professed "freelance monotheist," Karen

Armstrong. This quote sums up the single most influential argument

currently serving to deflect the accusation that Islam is inherently

violent and intolerant: All monotheistic religions, proponents of such an

argument say, and not just Islam, have their fair share of violent and

intolerant scriptures, as well as bloody histories. Thus, whenever Islam's

sacred scriptures—the Qur'an first, followed by the reports on the words

and deeds of Muhammad (the Hadith)—are highlighted as demonstrative of the

religion's innate bellicosity, the immediate rejoinder is that other

scriptures, specifically those of Judeo-Christianity, are as riddled with

violent passages.

More often than not, this argument puts an end to any

discussion regarding whether violence and intolerance are unique to Islam.

Instead, the default answer becomes that it is not Islam per se but

rather Muslim grievance and frustration—ever exacerbated by economic,

political, and social factors—that lead to violence. That this view

comports perfectly with the secular West's "materialistic" epistemology

makes it all the more unquestioned.

Therefore, before condemning the Qur'an and the historical

words and deeds of Islam's prophet Muhammad for inciting violence and

intolerance, Jews are counseled to consider the historical atrocities

committed by their Hebrew forefathers as recorded in their own scriptures;

Christians are advised to consider the brutal cycle of violence their

forbears have committed in the name of their faith against both

non-Christians and fellow Christians. In other words, Jews and Christians

are reminded that those who live in glass houses should not be hurling

stones.

But is that really the case? Is the analogy with other

scriptures legitimate? Does Hebrew violence in the ancient era, and

Christian violence in the medieval era, compare to or explain away the

tenacity of Muslim violence in the modern era?

Violence in Jewish and Christian History

Along with Armstrong, any number of prominent writers,

historians, and theologians have championed this "relativist" view. For

instance, John Esposito, director of the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Center

for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University, wonders,

How come we keep on asking the same question, [about

violence in Islam,] and don't ask the same question about Christianity

and Judaism? Jews and Christians have engaged in acts of violence. All

of us have the transcendent and the dark side. … We have our own

theology of hate. In mainstream Christianity and Judaism, we tend to be

intolerant; we adhere to an exclusivist theology, of us versus them.[2]

An article by Pennsylvania State University humanities

professor Philip Jenkins, "Dark Passages," delineates this position most

fully. It aspires to show that the Bible is more violent than the

Qur'an:

[I]n terms of ordering violence and bloodshed, any

simplistic claim about the superiority of the Bible to the Koran would

be wildly wrong. In fact, the Bible overflows with "texts of terror," to

borrow a phrase coined by the American theologian Phyllis Trible. The

Bible contains far more verses praising or urging bloodshed than does

the Koran, and biblical violence is often far more extreme, and marked

by more indiscriminate savagery. … If the founding text shapes the whole

religion, then Judaism and Christianity deserve the utmost condemnation

as religions of savagery.[3]

Several anecdotes from the Bible as well as from

Judeo-Christian history illustrate Jenkins' point, but two in

particular—one supposedly representative of Judaism, the other of

Christianity—are regularly mentioned and therefore deserve closer

examination.

The military conquest of the land of Canaan by the Hebrews

in about 1200 B.C.E. is often characterized as "genocide" and has all but

become emblematic of biblical violence and intolerance. God told

Moses:

But of the cities of these peoples which the Lord your God

gives you as an inheritance, you shall let nothing that breathes remain

alive, but you shall utterly destroy them—the Hittite, Amorite,

Canaanite, Perizzite, Hivite, and Jebusite—just as the Lord your God has

commanded you, lest they teach you to do according to all their

abominations which they have done for their gods, and you sin against

the Lord your God.[4]

So Joshua [Moses' successor] conquered all the land: the

mountain country and the South and the lowland and the wilderness

slopes, and all their kings; he left none remaining, but utterly

destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord, God of Israel had commanded.[5]

As for Christianity, since it is impossible to find New

Testament verses inciting violence, those who espouse the view that

Christianity is as violent as Islam rely on historical events such as the

Crusader wars waged by European Christians between the eleventh and

thirteenth centuries. The Crusades were in fact violent and led to

atrocities by the modern world's standards under the banner of the cross

and in the name of Christianity. After breaching the walls of Jerusalem in

1099, for example, the Crusaders reportedly slaughtered almost every

inhabitant of the Holy City. According to the medieval chronicle, the

Gesta Danorum, "the slaughter was so great that our men waded in

blood up to their ankles."[6]

In light of the above, as Armstrong, Esposito, Jenkins, and

others argue, why should Jews and Christians point to the Qur'an as

evidence of Islam's violence while ignoring their own scriptures and

history?

Bible versus Qur'an

The answer lies in the fact that such observations confuse

history and theology by conflating the temporal actions of men with what

are understood to be the immutable words of God. The fundamental error is

that Judeo-Christian history—which is violent—is being conflated with

Islamic theology—which commands violence. Of course, the three major

monotheistic religions have all had their share of violence and

intolerance towards the "other." Whether this violence is ordained by God

or whether warlike men merely wished it thus is the key question.

Old Testament violence is an interesting case in point. God

clearly ordered the Hebrews to annihilate the Canaanites and surrounding

peoples. Such violence is therefore an expression of God's will, for good

or ill. Regardless, all the historic violence committed by the Hebrews and

recorded in the Old Testament is just that—history. It happened; God

commanded it. But it revolved around a specific time and place and was

directed against a specific people. At no time did such violence go on to

become standardized or codified into Jewish law. In short, biblical

accounts of violence are descriptive, not prescriptive.

This is where Islamic violence is unique. Though similar to

the violence of the Old Testament—commanded by God and manifested in

history—certain aspects of Islamic violence and intolerance have become

standardized in Islamic law and apply at all times. Thus, while the

violence found in the Qur'an has a historical context, its ultimate

significance is theological. Consider the following Qur'anic verses,

better known as the "sword-verses":

Then, when the sacred months are drawn away, slay the

idolaters wherever you find them, and take them, and confine them, and

lie in wait for them at every place of ambush. But if they repent, and

perform the prayer, and pay the alms, then let them go their way.[7]

Fight those who believe not in God and the Last Day, and

do not forbid what God and His Messenger have forbidden – such men as

practise not the religion of truth, being of those who have been given

the Book – until they pay the tribute out of hand and have been

humbled.[8]

As with Old Testament verses where God commanded the Hebrews

to attack and slay their neighbors, the sword-verses also have a

historical context. God first issued these commandments after the Muslims

under Muhammad's leadership had grown sufficiently strong to invade their

Christian and pagan neighbors. But unlike the bellicose verses and

anecdotes of the Old Testament, the sword-verses became fundamental to

Islam's subsequent relationship to both the "people of the book" (i.e.,

Jews and Christians) and the "pagans" (i.e., Hindus, Buddhists, animists,

etc.) and, in fact, set off the Islamic conquests, which changed the face

of the world forever. Based on Qur'an 9:5, for instance, Islamic law

mandates that pagans and polytheists must either convert to Islam or be

killed; simultaneously, Qur'an 9:29 is the primary source of Islam's

well-known discriminatory practices against conquered Christians and Jews

living under Islamic suzerainty.

In fact, based on the sword-verses as well as countless

other Qur'anic verses and oral traditions attributed to Muhammad, Islam's

learned officials, sheikhs, muftis, and imams throughout the ages have all

reached consensus—binding on the entire Muslim community—that Islam is to

be at perpetual war with the non-Muslim world until the former subsumes

the latter. Indeed, it is widely held by Muslim scholars that since the

sword-verses are among the final revelations on the topic of Islam's

relationship to non-Muslims, that they alone have abrogated some 200 of

the Qur'an's earlier and more tolerant verses, such as "no compulsion is

there in religion."[9] Famous Muslim

scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) admired in the West for his "progressive"

insights, also puts to rest the notion that jihad is defensive

warfare:

In the Muslim community, the holy war [jihad] is a

religious duty, because of the universalism of the Muslim mission and

the obligation to convert everybody to Islam either by persuasion or by

force ... The other religious groups did not have a universal mission,

and the holy war was not a religious duty for them, save only for

purposes of defense ... They are merely required to establish their

religion among their own people. That is why the Israelites after Moses

and Joshua remained unconcerned with royal authority [e.g., a

caliphate]. Their only concern was to establish their religion [not

spread it to the nations] … But Islam is under obligation to gain power

over other nations.[10]

Modern authorities agree. The Encyclopaedia of

Islam's entry for "jihad" by Emile Tyan states that the "spread of

Islam by arms is a religious duty upon Muslims in general … Jihad must

continue to be done until the whole world is under the rule of Islam …

Islam must completely be made over before the doctrine of jihad [warfare

to spread Islam] can be eliminated." Iraqi jurist Majid Khaduri

(1909-2007), after defining jihad as warfare, writes that "jihad … is

regarded by all jurists, with almost no exception, as a collective

obligation of the whole Muslim community."[11] And, of course, Muslim legal manuals written in

Arabic are even more explicit.[12]

Qur'anic Language

When the Qur'an's violent verses are juxtaposed with their

Old Testament counterparts, they are especially distinct for using

language that transcends time and space, inciting believers to attack and

slay nonbelievers today no less than yesterday. God commanded the Hebrews

to kill Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and

Jebusites—all specific peoples rooted to a specific time and place. At no

time did God give an open-ended command for the Hebrews, and by extension

their Jewish descendants, to fight and kill gentiles. On the other hand,

though Islam's original enemies were, like Judaism's, historical (e.g.,

Christian Byzantines and Zoroastrian Persians), the Qur'an rarely singles

them out by their proper names. Instead, Muslims were (and are) commanded

to fight the people of the book—"until they pay the tribute out of hand

and have been humbled"[13] and to

"slay the idolaters wherever you find them."[14]

The two Arabic conjunctions "until" (hata) and

"wherever" (haythu) demonstrate the perpetual and ubiquitous nature

of these commandments: There are still "people of the book" who have yet

to be "utterly humbled" (especially in the Americas, Europe, and Israel)

and "pagans" to be slain "wherever" one looks (especially Asia and

sub-Saharan Africa). In fact, the salient feature of almost all of the

violent commandments in Islamic scriptures is their open-ended and generic

nature: "Fight them [non-Muslims] until there is no persecution and

the religion is God's entirely. [Emphasis added.]"[15] Also, in a well-attested tradition that appears in

the hadith collections, Muhammad proclaims:

I have been commanded to wage war against mankind

until they testify that there is no god but God and that Muhammad

is the Messenger of God; and that they establish prostration prayer, and

pay the alms-tax [i.e., convert to Islam]. If they do so, their blood

and property are protected. [Emphasis added.][16]

This linguistic aspect is crucial to understanding

scriptural exegeses regarding violence. Again, it bears repeating that

neither Jewish nor Christian scriptures—the Old and New Testaments,

respectively—employ such perpetual, open-ended commandments. Despite all

this, Jenkins laments that

Commands to kill, to commit ethnic cleansing, to

institutionalize segregation, to hate and fear other races and religions

… all are in the Bible, and occur with a far greater frequency than in

the Qur'an. At every stage, we can argue what the passages in question

mean, and certainly whether they should have any relevance for later

ages. But the fact remains that the words are there, and their inclusion

in the scripture means that they are, literally, canonized, no less than

in the Muslim scripture.[17]

One wonders what Jenkins has in mind by the word

"canonized." If by canonized he means that such verses are considered part

of the canon of Judeo-Christian scripture, he is absolutely correct;

conversely, if by canonized he means or is trying to connote that these

verses have been implemented in the Judeo-Christian Weltanschauung,

he is absolutely wrong.

Yet one need not rely on purely exegetical and philological

arguments; both history and current events give the lie to Jenkins's

relativism. Whereas first-century Christianity spread via the blood of

martyrs, first-century Islam spread through violent conquest and

bloodshed. Indeed, from day one to the present—whenever it could—Islam

spread through conquest, as evinced by the fact that the majority of what

is now known as the Islamic world, or dar al-Islam, was conquered

by the sword of Islam. This is a historic fact, attested to by the most

authoritative Islamic historians. Even the Arabian peninsula, the "home"

of Islam, was subdued by great force and bloodshed, as evidenced by the

Ridda wars following Muhammad's death when tens of thousands of Arabs were

put to the sword by the first caliph Abu Bakr for abandoning Islam.

Muhammad's Role

Moreover, concerning the current default position which

purports to explain away Islamic violence—that the latter is a product of

Muslim frustration vis-à-vis political or economic oppression—one must

ask: What about all the oppressed Christians and Jews, not to mention

Hindus and Buddhists, of the world today? Where is their

religiously-garbed violence? The fact remains: Even though the Islamic

world has the lion's share of dramatic headlines—of violence, terrorism,

suicide-attacks, decapitations—it is certainly not the only region

in the world suffering under both internal and external pressures.

For instance, even though practically all of sub-Saharan

Africa is currently riddled with political corruption, oppression and

poverty, when it comes to violence, terrorism, and sheer chaos,

Somalia—which also happens to be the only sub-Saharan country that is

entirely Muslim—leads the pack. Moreover, those most responsible for

Somali violence and the enforcement of intolerant, draconian, legal

measures—the members of the jihadi group Al-Shabab (the youth)—articulate

and justify all their actions through an Islamist paradigm.

In Sudan, too, a jihadi-genocide against the Christian and

polytheistic peoples is currently being waged by Khartoum's Islamist

government and has left nearly a million "infidels" and "apostates" dead.

That the Organization of Islamic Conference has come to the defense of

Sudanese president Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, who is wanted by the

International Criminal Court, is further telling of the Islamic body's

approval of violence toward both non-Muslims and those deemed not Muslim

enough.

Latin American and non-Muslim Asian countries also have

their fair share of oppressive, authoritarian regimes, poverty, and all

the rest that the Muslim world suffers. Yet, unlike the near daily

headlines emanating from the Islamic world, there are no records of

practicing Christians, Buddhists, or Hindus crashing explosives-laden

vehicles into the buildings of oppressive (e.g., Cuban or Chinese

communist) regimes, all the while waving their scriptures in hand and

screaming, "Jesus [or Buddha or Vishnu] is great!" Why?

There is one final aspect that is often overlooked—either

from ignorance or disingenuousness—by those who insist that violence and

intolerance is equivalent across the board for all religions. Aside from

the divine words of the Qur'an, Muhammad's pattern of behavior—his

sunna or "example"—is an extremely important source of legislation

in Islam. Muslims are exhorted to emulate Muhammad in all walks of life:

"You have had a good example in God's Messenger."[18] And Muhammad's pattern of conduct toward

non-Muslims is quite explicit.

Sarcastically arguing against the concept of moderate Islam,

for example, terrorist Osama bin Laden, who enjoys half the Arab-Islamic

world's support per an Al-Jazeera poll,[19] portrays the Prophet's sunna thusly:

"Moderation" is demonstrated by our prophet who did not

remain more than three months in Medina without raiding or sending a

raiding party into the lands of the infidels to beat down their

strongholds and seize their possessions, their lives, and their women.[20]

In fact, based on both the Qur'an and Muhammad's

sunna, pillaging and plundering infidels, enslaving their children,

and placing their women in concubinage is well founded.[21] And the concept of sunna—which is what 90

percent of the billion-plus Muslims, the Sunnis, are named

after—essentially asserts that anything performed or approved by Muhammad,

humanity's most perfect example, is applicable for Muslims today no less

than yesterday. This, of course, does not mean that Muslims in mass live

only to plunder and rape.

But it does mean that persons naturally inclined to such

activities, and who also happen to be Muslim, can—and do—quite easily

justify their actions by referring to the "Sunna of the Prophet"—the way

Al-Qaeda, for example, justified its attacks on 9/11 where innocents

including women and children were killed: Muhammad authorized his

followers to use catapults during their siege of the town of Ta'if in 630

C.E.—townspeople had refused to submit—though he was aware that women and

children were sheltered there. Also, when asked if it was permissible to

launch night raids or set fire to the fortifications of the infidels if

women and children were among them, the Prophet is said to have responded,

"They [women and children] are from among them [infidels]."[22]

Jewish and Christian Ways

Though law-centric and possibly legalistic, Judaism has no

such equivalent to the Sunna; the words and deeds of the patriarchs,

though described in the Old Testament, never went on to prescribe Jewish

law. Neither Abraham's "white-lies," nor Jacob's perfidy, nor Moses'

short-fuse, nor David's adultery, nor Solomon's philandering ever went on

to instruct Jews or Christians. They were understood as historical acts

perpetrated by fallible men who were more often than not punished by God

for their less than ideal behavior.

As for Christianity, much of the Old Testament law was

abrogated or fulfilled—depending on one's perspective—by Jesus. "Eye for

an eye" gave way to "turn the other cheek." Totally loving God and one's

neighbor became supreme law.[23]

Furthermore, Jesus' sunna—as in "What would Jesus do?"—is

characterized by passivity and altruism. The New Testament contains

absolutely no exhortations to violence.

Still, there are those who attempt to portray Jesus as

having a similarly militant ethos as Muhammad by quoting the verse where

the former—who "spoke to the multitudes in parables and without a parable

spoke not"[24]—said, "I come not to

bring peace but a sword."[25] But

based on the context of this statement, it is clear that Jesus was not

commanding violence against non-Christians but rather predicting that

strife will exist between Christians and their environment—a prediction

that was only too true as early Christians, far from taking up the sword,

passively perished by the sword in martyrdom as too often they still do in

the Muslim world. [26]

Others point to the violence predicted in the Book of

Revelation while, again, failing to discern that the entire account is

descriptive—not to mention clearly symbolic—and thus hardly prescriptive

for Christians. At any rate, how can one conscionably compare this handful

of New Testament verses that metaphorically mention the word "sword" to

the literally hundreds of Qur'anic injunctions and statements by Muhammad

that clearly command Muslims to take up a very real sword against

non-Muslims?

Undeterred, Jenkins bemoans the fact that, in the New

Testament, Jews "plan to stone Jesus, they plot to kill him; in turn,

Jesus calls them liars, children of the Devil."[27] It still remains to be seen if being called

"children of the Devil" is more offensive than being referred to as the

descendents of apes and pigs—the Qur'an's appellation for Jews.[28] Name calling aside, however, what

matters here is that, whereas the New Testament does not command

Christians to treat Jews as "children of the Devil," based on the Qur'an,

primarily 9:29, Islamic law obligates Muslims to subjugate Jews, indeed,

all non-Muslims.

Does this mean that no self-professed Christian can be

anti-Semitic? Of course not. But it does mean that Christian anti-Semites

are living oxymorons—for the simple reason that textually and

theologically, Christianity, far from teaching hatred or animosity,

unambiguously stresses love and forgiveness. Whether or not all Christians

follow such mandates is hardly the point; just as whether or not all

Muslims uphold the obligation of jihad is hardly the point. The only

question is, what do the religions command?

John Esposito is therefore right to assert that "Jews and

Christians have engaged in acts of violence." He is wrong, however, to

add, "We [Christians] have our own theology of hate." Nothing in the New

Testament teaches hate—certainly nothing to compare with Qur'anic

injunctions such as: "We [Muslims] disbelieve in you [non-Muslims], and

between us and you enmity has shown itself, and hatred for ever until you

believe in God alone."[29]

Reassessing the Crusades

And it is from here that one can best appreciate the

historic Crusades—events that have been thoroughly distorted by Islam's

many influential apologists. Karen Armstrong, for instance, has

practically made a career for herself by misrepresenting the Crusades,

writing, for example, that "the idea that Islam imposed itself by the

sword is a Western fiction, fabricated during the time of the Crusades

when, in fact, it was Western Christians who were fighting brutal holy

wars against Islam."[30] That a

former nun rabidly condemns the Crusades vis-à-vis anything Islam has done

makes her critique all the more marketable. Statements such as this ignore

the fact that from the beginnings of Islam, more than 400 years before the

Crusades, Christians have noted that Islam was spread by the sword.[31] Indeed, authoritative Muslim

historians writing centuries before the Crusades, such as Ahmad Ibn Yahya

al-Baladhuri (d. 892) and Muhammad ibn Jarir at-Tabari (838-923), make it

clear that Islam was spread by the sword.

The fact remains: The Crusades were a counterattack on

Islam—not an unprovoked assault as Armstrong and other revisionist

historians portray. Eminent historian Bernard Lewis puts it well,

Even the Christian crusade, often compared with the Muslim

jihad, was itself a delayed and limited response to the jihad and in

part also an imitation. But unlike the jihad, it was concerned primarily

with the defense or reconquest of threatened or lost Christian

territory. It was, with few exceptions, limited to the successful wars

for the recovery of southwest Europe, and the unsuccessful wars to

recover the Holy Land and to halt the Ottoman advance in the Balkans.

The Muslim jihad, in contrast, was perceived as unlimited, as a

religious obligation that would continue until all the world had either

adopted the Muslim faith or submitted to Muslim rule. … The object of

jihad is to bring the whole world under Islamic law.[32]

Moreover, Muslim invasions and atrocities against Christians

were on the rise in the decades before the launch of the Crusades in 1096.

The Fatimid caliph Abu 'Ali Mansur Tariqu'l-Hakim (r. 996-1021) desecrated

and destroyed a number of important churches—such as the Church of St.

Mark in Egypt and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem—and

decreed even more oppressive than usual decrees against Christians and

Jews. Then, in 1071, the Seljuk Turks crushed the Byzantines in the

pivotal battle of Manzikert and, in effect, conquered a major chunk of

Byzantine Anatolia presaging the way for the eventual capture of

Constantinople centuries later.

It was against this backdrop that Pope Urban II (r.

1088-1099) called for the Crusades:

From the confines of Jerusalem and the city of

Constantinople a horrible tale has gone forth and very frequently has

been brought to our ears, namely, that a race from the kingdom of the

Persians [i.e., Muslim Turks] … has invaded the lands of those

Christians and has depopulated them by the sword, pillage and fire; it

has led away a part of the captives into its own country, and a part it

has destroyed by cruel tortures; it has either entirely destroyed the

churches of God or appropriated them for the rites of its own

religion.[33]

Even though Urban II's description is historically accurate,

the fact remains: However one interprets these wars—as offensive or

defensive, just or unjust—it is evident that they were not based on the

example of Jesus, who exhorted his followers to "love your enemies, bless

those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who

spitefully use you and persecute you."[34] Indeed, it took centuries of theological debate,

from Augustine to Aquinas, to rationalize defensive war—articulated as

"just war." Thus, it would seem that if anyone, it is the Crusaders—not

the jihadists—who have been less than faithful to their scriptures (from a

literal standpoint); or put conversely, it is the jihadists—not the

Crusaders—who have faithfully fulfilled their scriptures (also from a

literal stand point). Moreover, like the violent accounts of the Old

Testament, the Crusades are historic in nature and not manifestations of

any deeper scriptural truths.

In fact, far from suggesting anything intrinsic to

Christianity, the Crusades ironically better help explain Islam. For what

the Crusades demonstrated once and for all is that irrespective of

religious teachings—indeed, in the case of these so-called Christian

Crusades, despite them—man is often predisposed to violence. But this begs

the question: If this is how Christians behaved—who are commanded to love,

bless, and do good to their enemies who hate, curse, and persecute

them—how much more can be expected of Muslims who, while sharing the same

violent tendencies, are further commanded by the Deity to attack, kill,

and plunder nonbelievers?

Raymond Ibrahim is associate director of the Middle

East Forum and author of The Al Qaeda Reader (New York:

Doubleday, 2007).

[1] Andrea Bistrich, "Discovering

the common grounds of world religions," interview with Karen

Armstrong, Share International, Sept. 2007, pp. 19-22.

[2] C-SPAN2, June 5, 2004.

[3] Philip Jenkins, "Dark

Passages," The Boston Globe, Mar. 8, 2009.

[4] Deut. 20:16-18.

[5] Josh. 10:40.

[6]

"The

Fall of Jerusalem," Gesta Danorum, accessed Apr. 2, 2009.

[7] Qur. 9:5. All translations of Qur'anic

verses are drawn from A.J. Arberry, ed. The

Koran Interpreted: A Translation (New York: Touchstone,

1996).

[8] Qur. 9:29.

[9] Qur. 2:256.

[10] Ibn Khaldun, The Muqudimmah: An Introduction to

History, Franz Rosenthal, trans. (New York: Pantheon, 1958,) vol. 1,

p. 473.

[11] Majid Khadduri,

War and Peace in the Law of Islam (London: Oxford University Press,

1955), p. 60.

[12] See, for

instance, Ahmed Mahmud Karima, Al-Jihad fi'l-Islam: Dirasa Fiqhiya

Muqarina (Cairo: Al-Azhar University, 2003).

[13] Qur. 9:29.

[14] Qur. 9:5.

[15] Qur. 8:39.

[16] Ibn al-Hajjaj Muslim, Sahih Muslim, C9B1N31;

Muhammad Ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari (Lahore: Kazi,

1979), B2N24.

[17] Jenkins, "Dark_Passages."

[18] Qur. 33:21.

[19] "Al-Jazeera-Poll:

49% of Muslims Support Osama bin Laden," Sept. 7-10, 2006, accessed

Apr. 2, 2009.

[20] 'Abd al-Rahim

'Ali, Hilf al Irhab (Cairo: Markaz al-Mahrusa li 'n-Nashr wa

'l-Khidamat as-Sahafiya wa 'l-Ma'lumat, 2004).

[21] For example, Qur. 4:24, 4:92, 8:69, 24:33,

33:50.

[22] Sahih Muslim,

B19N4321; for English translation, see Raymond Ibrahim, The Al Qaeda

Reader (New York: Doubleday, 2007), p. 140.

[23] Matt. 22:38-40.

[24] Matt. 13:34.

[25] Matt. 10:34.

[26] See, for instance, "Christian Persecution

Info," Christian Persecution Magazine, accessed Apr. 2,

2009.

[27] Jenkins, "Dark_Passages."

[28] Qur. 2:62-65, 5:59-60, 7:166.

[29] Qur. 60:4.

[30] Bistrich, "Discovering

the common grounds of world religions," pp. 19-22; For a critique of

Karen Armstrong's work, see "Karen

Armstrong," in Andrew Holt, ed. Crusades-Encyclopedia, Apr.

2005, accessed Apr. 6, 2009.

[31]

See, for example, the writings of Sophrinius, Jerusalem's patriarch during

the Muslim conquest of the Holy City, just years after the death of

Muhammad, or the chronicles of Theophane the Confessor.

[32] Bernard Lewis, The Middle East:

A Brief History of the Last 2000 Years (New York: Scribner, 1995), p.

233-4.

[33] "Speech

of Urban—Robert of Rheims," in Edward Peters, ed., The First

Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source

Materials (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), p.

27.

[34] Matt. 5:44. Related Topics: History, Islam, Jews and Judaism

Raymond

Ibrahim

To receive the full, printed version of the Middle

East Quarterly, please see details about an affordable subscription. |

No comments:

Post a Comment