Rahaf

Alqunun's Escape Spotlights Abuses Saudi Women Endure

by Abigail R. Esman

Special to IPT News

January 15, 2019

|

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the

first of your friends to like this. Be the

first of your friends to like this.

When Rahaf Mohammad

Alqunun barricaded herself in a Bangkok hotel room earlier this

month and took to Twitter, begging the world to protect her from being

forcibly sent home to Saudi Arabia, it was a desperate cry to save her own

life. But she also was speaking for millions of other Saudi women, whose

lives under patriarchal rule deprive them of their freedom, keeping them

permanently at risk of abuse, imprisonment, or even death. When Rahaf Mohammad

Alqunun barricaded herself in a Bangkok hotel room earlier this

month and took to Twitter, begging the world to protect her from being

forcibly sent home to Saudi Arabia, it was a desperate cry to save her own

life. But she also was speaking for millions of other Saudi women, whose

lives under patriarchal rule deprive them of their freedom, keeping them

permanently at risk of abuse, imprisonment, or even death.

Now Alqunun,18, has been granted asylum and is beginning a new life in

Canada. But her struggle does not end there.

Alqunun escaped from her parents Jan. 5 while on a family trip to

Kuwait, slipping from their sight onto a flight to Thailand. She had

endured years of horrific physical abuse at the hands of her parents,

including being locked in a room for six months and beaten. The reason:

they didn't like the way she'd cut her hair.

Yet by fleeing, she potentially faced even worse punishment from a

country where women are legally forbidden to travel without a male guardian

– usually their father or husband – and where girls who disobey their

fathers can go to jail. In the photographs she posted to

Twitter, she appears in a T-shirt with bare arms, and no veil – acts of

"immodesty" that conservative Muslims, and so, most Saudis –

consider a dishonor to the family. And women who dishonor their families

are likely to be killed by them; as Human Rights Watch deputy Middle East

director Michael Page told the New York Times, "Saudi women

fleeing their families can face severe violence from relatives, deprivation

of liberty, and other serious harm if returned against their will."

But even facing those dangers, the teen now risks another: "They

will kill me because I fled and because I announced my atheism. They wanted

me to pray and to wear a veil, and I didn't want to," she told the New York Times. In Saudi Arabia,

renouncing Islam is punishable by death.

Alqunun's story has

received worldwide attention and her courage has led many to hope that

international pressure will help incite change in the Kingdom. In a Twitter

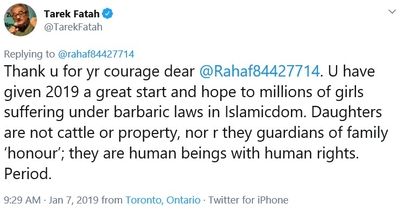

message directed to her, Canadian journalist and activist Tarek Fatah wrote: "Thank u for yr courage dear Alqunun's story has

received worldwide attention and her courage has led many to hope that

international pressure will help incite change in the Kingdom. In a Twitter

message directed to her, Canadian journalist and activist Tarek Fatah wrote: "Thank u for yr courage dear @Rahaf84427714.

U have given 2019 a great start and hope to millions of girls suffering

under barbaric laws in Islamicdom. Daughters are not cattle or property,

nor r they guardians of family 'honour'; they are human beings with human

rights. Period."

But Saudi Arabia's leaders, particularly Crown Prince Mohammad bin

Salman, are a long way from recognizing such basic human rights. A recent rush to arrest human rights activists, and women in

particular, testifies to this, along with a crackdown specifically on those

men and women who call for an end to the male guardianship system. Their

goal: to do away with a system under which women may not leave the home,

study, travel, marry, or even, apparently, cut their hair, without the

permission of their father or husband. As the New York Times noted, "Saudi men use a government website to

manage the women they have guardianship over, granting or denying them the

right to travel, for example, and even setting up notifications so that

they receive a text message when their wife or daughter boards a

plane."

Saudis take opposition to this system seriously. All the arrested

women's advocates stand accused of being national security threats and agents

of foreign governments. In prison, according to Amnesty International, those arrested have been "repeatedly

tortured by electrocution and flogging, leaving some unable to walk or

stand properly. In one reported instance, one of the activists was made to

hang from the ceiling, and according to another testimony, one of the

detained women was reportedly subjected to sexual harassment, by

interrogators wearing face masks."

Among them is Samar Badawi, whose brother Raif Badawi made

headlines after being sentenced to 10 years and 1,000 lashes for blog

postings the regime called "insulting to Islam." A longtime

fighter for the end of male guardianship, and the 2012 recipient of the

U.S. International Women of Courage Award, Samar Badawi was first arrested in 2010 for "disobeying" her

drug-addicted, abusive father by escaping to a women's shelter. Since then,

she has taken part in the fights to allow Saudi women to drive and for

freedom of dissent – all of which led to her latest arrest in July, together with another women's rights

activist, Nassima al Sadah. Both women are reportedly being held

incommunicado, although it is rumored that Samar Badawi is now at maximum

security Dhabhan prison, where her brother is also being held.

They are by no means the only ones. In May, officials arrested Loujain al-Hathloul, a social media star who

has also campaigned for the right to drive – even though the driving ban

had already been lifted. Al-Hathloul, 29, is known for driving

from the UAE into Saudi Arabia in 2014, an act for which she was charged

with terrorism and spent nearly three months in jail. Two years later, she

went further, signing a petition against male guardianship. For that, she

was "arrested without charge and...unable to contact her lawyer or

family members until she was eventually released shortly after," Al

Jazeera reported. And there are more activists: Amnesty

International last August counted a total of at least eight women and four men,

all being held without charge.

Yet despite all the arrests and the torture of such rights activists,

despite the ongoing atrocities perpetrated in the Saudi war in Yemen,

despite the murder of Washington Post reporter Jamal

Khashoggi, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (or "MBS," as he is

known) continues to position himself as a kind of reformer, a new, young

voice for a freer, more modern Saudi Arabia. And often he gets away with

it, hiding behind his simultaneous crackdown on ultraconservative religious

leaders, and by cozying up to Western world leaders, with money, oil, and

often just mere flattery.

And perhaps he even sees himself as such, for all his abuses. The cases

of women like Samar Bawadi and Rahaf Alqunun, their incarceration and

persecution both by their families and the state, articulate clearly the

extent to which patriarchal systems and views of women are entrenched not

just in Saudi culture, but in its psyche. This is a country where women now

may drive if the royal family says so, but they may not ask to have that

right in the first place. It is a country where a girl or woman (Badawi was

29) who disobeys her father commits a crime, where the government will

intervene to enforce her familial and legal place.

"I want to be protected in a country that will give me my rights

and allow me to live a normal life," Alqunun told the New York Times while still barricaded

in her Bangkok hotel room.

She now will have that chance. But her story shows that this kind of

happy ending is still a long time coming for the women she leaves behind.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in

the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in

New York and the Netherlands. Follow her at @radicalstates.

Related Topics: Abigail

R. Esman, Saudi

Arabia, women's

rights, Rahaf

Mohammad Alqunun, honor

crimes, Tarek

Fatah, Mohammad

bin Salman, Amnesty

International, Samar

Badawi, Raif

Badawi, Nassima

al Sadah, Loujain

al-Hathloul

|

No comments:

Post a Comment