|

|

Follow the Middle East Forum

|

|

Related Articles

Send Ground

Forces to Destroy ISIS?

The Coming

Strategic Stalemate

What was optimistically termed the "Arab spring" has since

evolved into what looks like a long and ghastly "jihadist winter,"

in which ISIS has seized the leading role for a number of reasons:The weakness of Iraqi and Syrian security forces. Even before ISIS's conquest of Ramadi (late 2014-early 2015) and Palmyra (May 2015), some 30,000 anti-ISIS troops and Shiite militia took a month's time and heavy casualties to retake the not-very-heavily defended town of Tikrit while the late 2015 Ramadi offensive took several months to recapture a largely deserted city held by a small number of ISIS defenders.[1] A large part of the regular Iraqi security forces (ISF) will need to be comprehensively rebuilt, a task widely expected to take years.[2] Anti-ISIS militias, with the possible exception of Hezbollah, are generally much better at defending than attacking and have not been notably effective on the offensive. For example, in the battle for Tikrit in March 2015, while the Shiite militias claimed they were being deliberately slow in their advance, this was probably just doublespeak to explain lack of progress due to heavy casualties on the ground.[3] While usually more highly rated as fighters, the Kurdish militias may also be of uncertain capability.[4] In any case, it is questionable whether the Kurdish peshmerga will be willing to expend lives capturing traditionally ethnic Arab areas from ISIS except for those parts they might ultimately want to include in an independent Kurdish state. In Syria, Assad regime forces, heavily supported by Russia as well as Iran and its Hezbollah and other Shiite proxies, and its Hezbollah proxy, have been unable to do much more than maintain a stalemate with the very fragmented insurgents. The burgeoning Russian intervention, which has not yet fully engaged ISIS, is unlikely to do much more than escalate the stalemate be-cause the Assad regime has admitted that its basic problem is a lack of manpower, and Russian air strikes and a couple thousand Iranian and Hezbollah fighters will not change that.[5]

The consolidation of control. ISIS has established a minimally functional governing regime in the areas it controls and has ruthlessly worked to suppress or co-opt any potential opposition in those areas.[9] So far, it has managed to avoid provoking a major rebellion of the Sunni Arab tribes as happened in the 2006 "Anbar Awakening" during the previous round of the Iraqi civil war. Even if a popular rebellion were to arise that ISIS could not immediately suppress, the most likely result would be a situation parallel to Syria with a multi-sided civil war in which ISIS would be at least strong enough to maintain control over significant areas. Any major at-tempt by a fundamentally unreformed Iraqi government to retake Sunni Arab majority areas—especially if attempted by Shiite militias or Iranian troops—is all too likely to be viewed by the Sunnis as an attempted re-conquest by a hostile Shiite regime.[10] Since many of the Shiite militias can be as enthusiastically murderous as ISIS,[11] Iraq's Sunni Arabs may likely see it as a war of intended extermination.[12] Certainly in Syria, the Assad regime's war is already viewed that way. It remains to be seen if Iraqi prime minister Haider Abadi will be able to reform the Iraqi government enough to appeal to non-ISIS Sunni Arabs. As of this writing, the results do not look promising as the Iraqi government, increasingly challenged by militant Shiite factions (e.g., the Sadrists), has been at best reluctant to support Sunni Arab forces, at worst, has removed Sunni Arab officers from the Iraqi security forces, and is struggling to avoid collapse.[13]

A wider threat. The Islamic State will also pose a major threat to Europe and the United States, driven as it is by a global jihadist mission with its self-proclaimed caliph, Abu Bakr Baghdadi, justifying his position by right of conquest in a worldwide religious war.[16] It should be remembered that al-Qaeda's ideology, from which ISIS doctrine is largely derived, has always been one of world conquest, intending the subjugation of the international community to the rule of Islam.[17] In the words of Sheikh Abu Muhammad Adnani ash-Shami, ISIS spokesperson: We will conquer your Rome, break your crosses, and enslave your women, by the permission of Allah, the Exalted. This is His promise to us; He is glorified and He does not fail in His promise. If we do not reach that time, then our children and grandchildren will reach it, and they will sell your sons as slaves at the slave market.[18]

Since many or most foreign recruits are attracted to ISIS's extreme violence and fanaticism, their willingness to engage in terrorism if and when they return to their countries of origin is to be expected. Baghdadi has already threatened to stage a mass-casualty attack against the United States.[20] Whether this is just the natural outgrowth of his jihadist mentality, an attempt to deter Washington from expanding its anti-ISIS operations, or conversely, to provoke it and thereby advance the narrative of a U.S. war against Islam, is immaterial.[21] The November 2015 Paris attacks and the March 2016 Brussels bombings may very well be the Islamic State's coming out party in the West. There is an increasing likelihood, especially if boxed into a corner, that ISIS will do something so monstrous that it will make a major U.S. intervention unavoidable as was the case with al-Qaeda in Afghanistan after 9/11.

Mainstreaming

Jihadism and "Martyrdom"

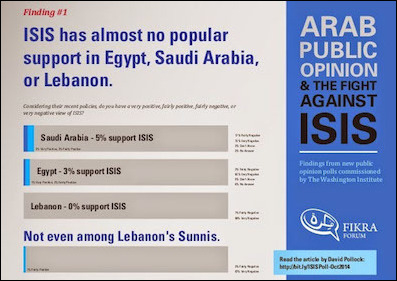

While polling indicates that jihadists in general have continued to retain

a degree of support in both Muslim-majority countries and among Muslims

world-wide,[22] there

seems not to have been a massive groundswell of popular support for ISIS,

either within Iraq, Muslim-majority countries, or the world at large In a

poll reported by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, 94

percent of those polled in Iraq, including Sunni Arabs, considered ISIS a

terrorist organization, as did 82 percent of Yemenis, 73 percent of

Jordanians, 72 percent of Syrians, and 72 percent of Libyans. ISIS is also

reported to have almost no support in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, or Egypt.[23] It was only in Syria that a

significant minority (27 percent of people polled) did not consider it a

terrorist group. This polling was reported to include people in areas

occupied by ISIS.

Should ISIS man-age to survive in its territory and consolidate its rule, one must expect to see over time the "mainstreaming of jihadism." Within areas it controls, considerable portions of the society, especially young males—the "cubs of the Caliphate"[25]—will be indoctrinated to think in jihadist terms even if they did not when ISIS took over initially.[26] Ultimately, this will produce both a cadre of fighters and, to some degree, a society that will embrace the jihadist assumption that dying in battle to defend—or advance—the Islamic State against those defined as enemies of Islam is an honorable if not a preferred death. Should the West engage ISIS in ground combat at such a time, it must be prepared to deal with a militarized regime and, to some degree, a population of religious fanatics who will be prepared to die fighting rather than surrender. This must be seen as a paradigm shift in the use of suicide tactics. Until the emergence of ISIS, such tactics were largely the equivalent of special operations. A single person or a small team of suicide bombers, either alone or in coordination with others, would attempt to reach a target before setting off the bomb. But suicide tactics have never been used routinely in conventional or even irregular warfare with the exception of the Japanese World War II Kamikaze attacks and Tehran's "human waves" tactics during the Iran-Iraq war where thousands of children were sacrificed to clear Iraqi minefields.[27]

So far the Obama administration's strategy of air strikes, retraining the Iraqi security forces, rebuilding Sunni support in Iraq, and backing "moderate" Syrian factions shows few signs of success. Even if the Iraqi government is able to reform enough to attract some support from its Sunni Arab citizenry, to rebuild its army and government-aligned forces into effective offensive forces, and to reconstruct the conditions that enabled the Sunni tribal uprising against ISIS's predecessors—three very big "ifs"—it remains to be seen if this strategy will ultimately work. All things considered, it is all too likely to fail in due course.[30] Other regional forces such as the Turks, Saudis, and Jordanians so far show no sign of being willing to provide a major commitment of ground troops, and any major intervention by the Iranians will likely drive Sunni Arabs further into the arms of ISIS. Washington and its allies must then decide whether they are willing to settle for merely containing ISIS. In practical terms, this means accepting both the dismemberment of Iraq and Syria and the ongoing threat that ISIS will seek to acquire weapons of mass destruction.[31] If ISIS's opponents choose to be proactive (or, more likely, reactive as a result of massive provocation), it is critical to think long and hard about what strategy and tactics will need to be used against an enemy like the Islamic State. [32]

Confronting

Fighting to the Death

It is, of course, possible that ISIS will not embrace a strategy of

fighting to the death as a routine matter;[33] at the Battle of Tora Bora in

2001, for example, Osama Bin Laden authorized his surviving men to surrender.[34] But anyone who considers fighting

a consolidated ISIS on the ground, especially in major urban centers, must

expect a grim struggle against a dug-in enemy. Troops deployed into such a

scenario must work under the assumption that not only enemy combatants but

also civilians may intend to kill them or die trying.

The preferred U.S strategy of rapid and decisive victory will be irrelevant. This strategy is based on the use of superior U.S. military technology and precise firepower, especially airpower, to stun the enemy, disrupt its government and military, inflict strategic and operational paralysis, destroy its will to resist, and enable U.S. and allied forces to win decisively and quickly with minimal friendly losses and limited enemy losses and collateral damage. This is un-likely to work against a jihadist government and society. For ISIS militants and those parts of society it has radicalized, religious fervor is likely to make their will extraordinarily resistant to collapse as they will consider fighting and dying a religious duty. Militarily, even if U.S. forces are somehow able to paralyze the ISIS command structure—a presumption not borne out by observation of their behavior in the field as the organization has demonstrated an extremely resilient military and political command structure[38]—it will be immaterial at the tactical level. At that level, militants will either regard them-selves as undefeated, will expect to die even if defeated, or both.[39]

The ground war will need to be slow and methodical. Western forces should not expect a "race to Baghdad," an air-to-ground blitzkrieg operational strategy, to be successful. Attacking forces will need to be prepared to literally dig out and kill every defender. This may mean a return to tactics of annihilation based on massive rather than precision firepower or to a tactic based on massive, precision firepower. Since enemy troops in cut-off or bypassed units and positions will likely be prepared to die in place, they will need to be treated not as defeated remnants but as bypassed centers of resistance. Mopping up cannot be treated as an afterthought, and such enemy units and positions will need to be tightly encircled and contained until destroyed, which will require a large force of ground troops and large munition supplies. Rear areas will need to be carefully secured. One study proposed a force of 25,000 ground troops.[42] Unless such forces can be supplemented with large numbers of competent local troops, this, also, is likely to be too small a number.

As a result, war at the tactical level will be even grimmer than usual. E.B. Sledge, in his classic work With the Old Breed (about Marines in the Pacific in World War II), noted that frontline infantrymen hated the Japanese troops with a raw passion, due in part to the Japanese use of the same kinds of tactics ISIS jihadists are likely to use, for example, "playing dead and then throwing a grenade, or playing wounded, calling for a corpsman, and then knifing the medic when he came".[44] Since the hatred was mutual, this led to savage and ferocious kill-or-be-killed fighting. Although this attitude did not extend to enemy civilians, it is reasonable to expect that if civilians had joined the fighting and used such tactics, they would have been treated the same way by U.S. troops. If ISIS militants and civilians use tactics like these, it is likely to lead to the same kind of attitudes and the same type of fighting. Even if parts or most of society are opposed to ISIS and are prepared to welcome or not resist anti-ISIS troops, how many false surrenders or attacks by civilians will it take to poison the well, so that in the interest of survival, Western troops begin to shoot first and ask questions later? Information operations will be critical. If the West fights a ground war with ISIS, it must expect to operate in a virulently hostile media environment where many Muslims and their Western acolytes will be eager to believe that the West is wantonly murdering innocent civilians. At the strategic communication level, the public and troops need advance warning of the nature of the enemy, the war they are facing, and the tactics ISIS routinely uses. It will need to be clear that fighting this kind of war is not the West's preference, but if ISIS decides to fight such a war—with routine use of military and civilian suicide tactics—the West will have no choice but to respond as outlined here with extensive destruction and likely massive numbers of civilian casualties an inevitable result.

Reappraising

International Laws of War

Beginning in the nineteenth century, if not earlier, the West has come to

esteem a series of treaties and declarations that have been termed the

"laws of war." Certain behaviors have been deemed unacceptable both

in armed conflict and in behavior toward civilians during times of war. In

the late twentieth century, there emerged a general consensus of what could

and could not be done to one's enemy even during war.

Facing such a foe requires readdressing the perennial legal issues posed by warfare with totalitarian states that are utterly contemptuous of the laws of armed conflict and proud of that contempt. If the jihadist state wages war as a total war, with no distinction between military and civilians, will it be possible for the West not to wage one as well? When fighting jihadists, should clerics be automatically defined as noncombatants and religious sites as non-targetable even though both may well be regularly and directly involved in combat operations? If a madrasa (Islamic school) provides military training to its students, or a mosque is used as a weapon depot or as a base for an ISIS unit, does that make them legitimate targets? Should one even consider taking prisoners if those surrendering may actually only want to get close enough to kill the people trying to capture them? Can ISIS's wounded be treated if those wounded try to kill the medical personnel treating them? Clearly, Western powers contemplating taking on such an enemy need to examine the international law and war crimes issue before engaging in combat, lest their enemies use "lawfare" against them in spite of the undisguised criminality of ISIS.[45]

The Strategic

Future

Deterrence relies on persuading an enemy that the costs of doing something

exceed the likely benefits. But how does one deter an enemy who views the

status quo as a crime against God, whose strategy is based on a willingness

to die, and who believes that the act of dying is its own reward? Washington

and the rest of the West should not expect strategies of deterrence by

punishment—nor deterrence based on persuading the enemy that its efforts will

fail—to work. As with al-Qaeda, any expectation of dissuading such an enemy

from its goals is delusional.This kind of warfare will differ dramatically from anything the United States has faced recently. How does one fight not only armies but potentially parts of society that mean it when they say they will fight to the last and are even eager to do so? How is it possible to differentiate between combatants and noncombatants when the enemy intends to blur or obliterate the line between the two? And perhaps most problematic, how does one wage war against a foe willing to deliberately expend masses of civilians as a combat tactic and whose civilians may actually be willing to die in support of the regime?

A war with ISIS has ample potential to be a long and incredibly nasty war. The dynamism and relative success of ISIS continues to draw a steady stream of foreign recruits, especially younger jihadists.[47] Even if ISIS in its current form is defeated on the battlefield, the aftermath of the conflict will require a comprehensive occupation, a major rebuilding campaign after the fighting, a comprehensive "de-jihadization" of the society, and extensive war crimes trials. If undertaken and mishandled by what eventuates as Iraqi or Syrian authorities, de-jihadization and war crimes trials could become a cover for a massive vendetta against Sunni Arabs, which will just reignite the situation. Foreign "Christian" powers will be ill-suited to operate persuasively and effectively in such a setting. At the same time, the West should not underestimate the ability of the jihadists to self-destruct and defeat themselves as they have done with impressive regularity as in Algeria and the 2006 "Anbar Awakening" during the previous round of the Iraqi civil war. But no one should count on that happening. This is an enemy who sometimes learns from his mistakes. So, prudence alone demands that Western powers considering action ought to at least start thinking about how to deal with the worst case if it occurs. During the euphoric days of the "Arab spring," many fervently hoped that the Muslim Middle East was finally about to start moving forward to the "broad sunlit uplands" looked forward to by Winston Churchill during Britain's darkest hour. Tragically, but not surprisingly, that did not happen. If anything, the Muslim Middle East—and the world—will be very lucky if it does not move any further into the dark bloody highlands than it already has. But it would not be prudent to bet that it will not. Thomas R. McCabe is a retired Defense Department analyst and a retired U.S. Air Force reserve lieutenant colonel who worked ten years as a Middle East military analyst and two years as a counterterrorism analyst. This article represents his work and should not be considered the opinion of any agency of the U.S. government. [2] Reuters, Jan. 11, 2015; Anna Mulrine, "Pentagon says it will take years to retrain Iraqi forces. Why so long?" The Christian Science Monitor, Sept. 25, 2014. [3] WorldNews (WN) Network, Jan. 2, 2015; McClatchy DC (Washington, D.C.), July 16, 2014; BBC, Mar. 23, 2015. [4] Los Angeles Times, Oct. 9, 2014. [5] Vice News (New York), July 26, 2015. [6] McClatchy, Apr. 20, 2015. [7] Bill Roggio, "On the CIA Estimate of Number of Fighters in the Islamic State," Threat Matrix Blog, The Long War Journal (Washington, D.C.), Sept. 13, 2014; for larger estimates, see The Independent (London), Nov. 16, 2014. [8] Bing West, No True Glory (New York: Bantam Dell, 2005), pp. 268-316. [9] Spiegel-Online (Hamburg), Apr. 18, 2015. [10] See Sterling Jensen, "Fall of Anbar Province," Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2016. [11] Aki Peritz, "Self-Defeating Brutality: Why a war without mercy against ISIS is destined to fail," Slate (New York and Washington, D.C.), May 4, 2015; The Guardian (London), Aug. 24, 2014. [12] Reuters, Dec. 17, 2014. [13] "Background Briefing on Iraq," U.S. State Department, Washington, D.C., May 20, 2015; Michael Pregent and Robin Simcox, "Baghdad's Policy of Failure," Foreign Affairs, June 9, 2015; The Hill (Washington, D.C.), Dec. 11, 2015. [14] Robert Beckhusen, "Why Iraq War III Is Headed into a Long, Bloody Stalemate," War Is Boring Blog, June 15, 2014; Bill Ardolino and Bill Roggio, "Analysis: Protracted Struggle Ahead for Iraq," The Long War Journal, June 24, 2014. [15] "From the Battle of al-Ahzab to the War of Coalitions," DABIQ, al-Hayat Media Center, ISIS, Aug. 2015, p. 52. [16] Jihadist News, SITE Intelligence Group, Bethesda, Md., June 29, 2014. [17] "Reflections on the Final Crusade," DABIQ, Oct. 2014; Ayman Zawahiri, Knights under the Prophet's Banner, published in Asharq al-Awsat (London), n.d., accessed Mar. 12, 2015. [18] "In the Name of Allah the Beneficent the Merciful, Indeed Your Lord Is Ever Watchful," ISIS message, Sept. 26, 2014, accessed June 1, 2015. [19] Robert Spencer, "Islamic State: "If Allah wills, we will kill those who worship stones in Mecca and destroy the Kaaba," Jihad Watch, June 30, 2014; Vocativ (New York), July 8, 2014; International Business Times (New York), Oct. 9, 2014; "The Islamic State Founders on Signs of the Hour," DABIQ, Oct. 2014, p. 35. [20] John Cantile, "The Perfect Storm," DABIQ, May-June 2015, p. 77. [21] The New York Times, Aug. 10, 2014. [22] "Concerns about Islamic Extremism on the Rise in Middle East," Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C., July 1, 2014; "Muslim Americans: No Signs of Growth in Alienation or Support for Extremism," ibid., Aug. 2011. [23] Munqith M. Dagher, "Public Opinion towards Terrorist Organizations in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Libya: A special focus on Dai'sh in Iraq," briefing, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C., Mar. 4, 2015; David Pollock, "ISIS Has Almost No Popular Support in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, or Lebanon," The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, D.C., Oct. 14, 2014. [24] The Washington Post, July 13, 2014; David Ignatius, "Losing to the Islamic State," Real Clear Politics (Washington, D.C.), Oct. 24, 2014. [25] Charles C. Caris and Samuel Reynolds, "ISIS Governance in Syria," Institute for the Study of War, Washington, D.C., July 2014; Global News (Burnaby, B.C.), Oct. 29, 2014; The Independent, Feb. 23, 2015; BBC, Oct. 8, 2015. [26] Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 28, 2015. [27] Jonathan C. Randal, "Iran-Iraq War," Crimes of War Project, 2011. [28] Alexandre Mello and Michael Knights, "The Cult of the Offensive: The Islamic State on Defense," CTC Sentinel, Combating Terrorism Center, West Point, N.Y., Apr. 30, 2015; "The Devastating Islamic State Suicide Strategy," TSG IntelBrief, Soufan Group, New York, May 29, 2015. [29] Patrick Tucker, "The Islamic State Is Losing the Twitter War," Defense One (Washington, D.C.), Sept. 12, 2014; Peter Van Buren, "Islamic State's rules of attraction, and why U.S. countermoves are doomed," Reuters, Oct. 21, 2014. [30] Anthony H. Cordesman, "A Public Relations Exercise without Meaningful Transparency," Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C., May 1, 2015. [31] National Defense (Arlington), Oct. 7, 2014; BBC, Sept. 11, 2015. [32] Todd Johnson, "A Ground War against ISIL," Defense News (Springfield, Va.), Apr. 27, 2015. [33] Jessica McFate, "The ISIS Defense in Iraq and Syria, Countering an Adaptive Enemy: Middle East Security Report 27," Institute for the Study of War, Washington, D.C., May 2015. [34] Peter Bergen, "The Battle for Tora Bora: The Account of How We Nearly Caught Osama bin Ladin in 2001," The New Republic, Dec. 30, 2009. [35] Kate Brannen, "Children of the Caliphate," Foreign Policy, Oct. 27, 2014; Global News, Oct. 29, 2014. [36] The Washington Post, July 16, 2014; "The Islamic State's Population Shields," TSG IntelBrief, Soufan Group, New York, Apr. 13, 2015. [37] The New York Times, May 26, 2015. [38] Gary Anderson, "Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the Theory and Practice of Jihad," Small Wars Journal (Bethesda, Md.), Aug. 12, 2014; Austin Long, "The Foreign Policy Essay: The Islamic State's War Machine," The Lawfare Blog, Brookings Institute, Washington, D.C., Sept. 28, 2014; The Fiscal Times (New York), Oct. 10, 2014. [39] Kevin Woods and Mark Stout, "Saddam's Perceptions and Misperceptions: The Case of 'Desert Storm,'" Journal of Strategic Studies, Feb. 2010, pp. 5-42. [40] David Deptula, "Bombing Our Way to Victory," The Washington Post, June 6, 2015. [41] Shane Dixon Kavanaugh, "ISIS' Bulging Cash Cow: Shakedowns, Not Oil and Artifacts," Vocativ, Oct. 7, 2015. [42] Kimberly Kagan, Frederick W. Kagan, and Jessica D. Lewis, "A Strategy to Defeat the Islamic State," Middle East Security, report 23, Institute for the Study of War, Washington, D.C., Sept. 2014. [43] United Press International, Sept. 9, 2014. [44] E.B. Sledge, With the Old Breed (New York, Presidio [Random House], 2007), p. 39. [45] "Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic," United Nations, Geneva, Nov. 14, 2014. [46] Efraim Karsh, Islamic Imperialism: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, rev. ed., 2013), pp. 242-50; Salim Mansur, "ISIS, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the West," Gatestone Institute, New York, June 14, 2015. [47] The Washington Post, Dec. 20, 2014. |

||||||||||||||

|

To subscribe to the MEF mailing lists, go to http://www.meforum.org/list_subscribe.php |

No comments:

Post a Comment