Please take a moment to

visit and log in at the subscriber

area, and submit your city & country location. We will use this

information in future to invite you to any events that we organize in

your area.

Islam's

'Protestant Reformation'

by Raymond Ibrahim

PJ Media

June 20 and 27, 2014

Be the first of

your friends to like this. Be the first of

your friends to like this.

Originally published by PJ Media in two

parts.

In order to prevent a clash of civilizations, or worse, Islam must

reform. This is the contention of many Western peoples. And, pointing to

Christianity's Protestant Reformation as proof that Islam can also

reform, many are optimistic.

Overlooked by most, however, is that Islam has been reforming.

What is today called "radical Islam" is the reformation

of Islam. And it follows the same pattern of Christianity's Protestant

Reformation.

The problem is our understanding of the word "reform."

Despite its positive connotations, "reform" simply means

to "make changes (in something, typically a social, political, or

economic institution or practice) in order to improve it."

Synonyms of "reform" include "make better,"

"ameliorate," and "improve"—splendid words all, yet

words all subjective and loaded with Western references.

Muslim notions of "improving" society may include purging it

of "infidels" and their corrupt ways; or segregating men and

women, keeping the latter under wraps or quarantined at home; or

executing apostates, who are seen as traitorous agitators.

Banning many forms of freedoms taken for granted in the West—from

alcohol consumption to religious and gender equality—can be deemed an

"improvement" and a "betterment" of society.

In short, an Islamic reformation need not lead to what we think of as

an "improvement" and "betterment" of society—simply

because "we" are not Muslims and do not share their reference

points and first premises. "Reform" only sounds good to most

Western peoples because they, secular and religious alike, are to a great

extent products of Christianity's Protestant Reformation; and so, a

priori, they naturally attribute positive connotations to the word.

----

At its core, the Protestant Reformation was a revolt against tradition

in the name of scripture—in this case, the Bible. With the coming of the

printing press, increasing numbers of Christians became better acquainted

with the Bible's contents, parts of which they felt contradicted what the

Church was teaching. So they broke away, protesting that the only

Christian authority was "scripture alone," sola scriptura.

Islam's reformation follows the same logic of the Protestant

Reformation—specifically by prioritizing scripture over centuries of

tradition and legal debate—but with antithetical results that reflect the

contradictory teachings of the core texts of Christianity and Islam.

As with Christianity, throughout most of its history, Islam's scriptures,

specifically its "twin pillars," the Koran (literal words of

Allah) and the Hadith (words and deeds of Allah's prophet, Muhammad),

were inaccessible to the overwhelming majority of Muslims. Only a few

scholars, or ulema—literally, "they who know"—were

literate in Arabic and/or had possession of Islam's scriptures. The

average Muslim knew only the basics of Islam, or its "Five

Pillars."

In this context, a "medieval synthesis" flourished

throughout the Islamic world. Guided by an evolving general consensus (or

ijma'), Muslims sought to accommodate reality by, in medieval

historian Daniel Pipes' words,

translat[ing] Islam from a body of abstract, infeasible demands [as

stipulated in the Koran and Hadith] into a workable system. In practical

terms, it toned down Sharia and made the code of law operational. Sharia

could now be sufficiently applied without Muslims being subjected to its

more stringent demands… [However,] While the medieval synthesis worked

over the centuries, it never overcame a fundamental weakness: It is

not comprehensively rooted in or derived from the foundational,

constitutional texts of Islam. Based on compromises and half measures, it

always remained vulnerable to challenge by purists (emphasis added).

This vulnerability has now reached breaking point: millions of more

Korans published in Arabic and other languages are in circulation today

compared to just a century ago; millions of more Muslims are now literate

enough to read and understand the Koran compared to their medieval

forbears. The Hadith, which contains some of the most intolerant

teachings and violent deeds attributed to Islam's prophet, is now

collated and accessible, in part thanks to the efforts of Western

scholars, the Orientalists. Most recently, there is the Internet—where

all these scriptures are now available in dozens of languages and to

anyone with a laptop or iPhone.

In this backdrop, what has been called at different times, places, and

contexts "Islamic fundamentalism," "radical Islam,"

"Islamism," and "Salafism" flourished. Many of

today's Muslim believers, much better acquainted than their ancestors

with the often black and white words of their scriptures, are protesting

against earlier traditions, are protesting against the "medieval

synthesis," in favor of scriptural literalism—just like their

Christian Protestant counterparts once did.

Thus, if Martin Luther (d. 1546) rejected the extra-scriptural

accretions of the Church and "reformed" Christianity by

aligning it more closely with scripture, Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab (d.

1787), one of Islam's first modern reformers, "called for a return

to the pure, authentic Islam of the Prophet, and the rejection of the

accretions that had corrupted it and distorted it," in the words of

Bernard Lewis (The Middle East, p. 333).

The unadulterated words of God—or Allah—are all that matter for the

reformists.

Note: Because they are better acquainted with Islam's scriptures,

other Muslims, of course, are apostatizing—whether by converting to other

religions, most notably Christianity, or whether by abandoning religion

altogether, even if only in their hearts (for fear of the apostasy

penalty). This is an important point to be revisited later. Muslims who

do not become disaffected after better acquainting themselves with the

literal teachings of Islam's scriptures and who instead become more

faithful to and observant of them are the topic of this essay.

-----

How Christianity and Islam can follow similar patterns of reform but

with antithetical results rests in the fact that their scriptures are

often antithetical to one another. This is the key point, and one

admittedly unintelligible to postmodern, secular sensibilities, which

tend to lump all religious scripture together in a melting pot of

relativism without bothering to evaluate the significance of their

respective words and teachings.

Obviously a point-by-point comparison of the scriptures of Islam and

Christianity is inappropriate for an article of this length (see my

"Are

Judaism and Christianity as Violent as Islam" for a more

comprehensive treatment).

Suffice it to note some contradictions (which will be rejected as a

matter of course by the relativistic mindset):

· The New Testament preaches peace, brotherly love, tolerance, and

forgiveness—for all humans, believers and non-believers alike. Instead of

combatting and converting "infidels," Christians are called to

pray for those who persecute them and turn the other cheek (which is not

the same thing as passivity, for Christians are also called to be bold

and unapologetic). Conversely, the Koran and

Hadith call for war, or jihad, against all non-believers, until they

either convert, accept subjugation and discrimination, or die.

· The New Testament has no punishment for the apostate from

Christianity. Conversely, Islam's prophet himself decreed

that "Whoever changed his Islamic religion, then kill him."

· The New Testament teaches monogamy, one husband and one wife,

thereby dignifying the woman. The Koran

allows polygamy—up to four wives—and the possession of concubines, or

sex-slaves. More literalist readings treat

women as possessions.

· The New Testament discourages lying (e.g., Col. 3:9). The Koran permits

it; the prophet himself often deceived others, and permitted lying to

one's wife, to reconcile quarreling parties, and to the

"infidel" during war.

It is precisely because Christian scriptural literalism lends itself

to religious freedom, tolerance, and the dignity of women, that Western

civilization developed the way it did—despite the nonstop propaganda

campaign emanating from academia, Hollywood, and other major media that

says otherwise.

And it is precisely because Islamic scriptural literalism is at odds

with religious freedom, tolerance, and the dignity of women, that Islamic

civilization is the way it is—despite the nonstop propaganda campaign

emanating from academia, Hollywood, and other major media that says

otherwise.

----

Those in the West waiting for an Islamic "reformation" along

the same lines of the Protestant Reformation, on the assumption that it

will lead to similar results, must embrace two facts: 1) Islam's

reformation is well on its way, and yes, along the same lines of the

Protestant Reformation—with a focus on scripture and a disregard for

tradition—and for similar historic reasons (literacy, scriptural

dissemination, etc.); 2) But because the core teachings of the scriptures

of Christianity and Islam markedly differ from one another, Islam's

reformation has naturally produced a civilization markedly different from

the West.

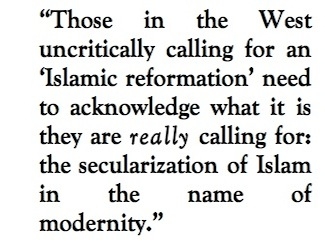

Put differently, those in the West uncritically calling for an

"Islamic reformation" need to acknowledge what it is they are really

calling for: the secularization of Islam in the name of modernity; the

trivialization and sidelining of Islamic law from Muslim society.

That would not be a "reformation"—certainly nothing

analogous to the Protestant Reformation.

Overlooked is that Western secularism was, and is, possible only

because Christian scripture lends itself to the division between church

and state, the spiritual and the temporal.

Upholding the literal teachings of Christianity is possible within a

secular—or any—state. Christ called on believers to "render unto

Caesar the things of Caesar (temporal) and unto God the things of God

(spiritual)" (Matt. 22:21). For the "kingdom of God" is

"not of this world" (John 18:36). Indeed, a good chunk of the

New Testament deals with how "man is not justified by the works of

the law… for by the works of the law no flesh shall be justified" (Gal.

2:16).

On the other hand, mainstream Islam is devoted to upholding the law;

and Islamic scripture calls for a fusion between Islamic law—Sharia—and

the state. Allah decrees in the Koran that "It is not fitting for

true believers—men or women—to take their choice in affairs if Allah and

His Messenger have decreed otherwise. He that disobeys Allah and His

Messenger strays far indeed!" (33:36). Allah tells the prophet of

Islam, "We put you on an ordained way [literarily in Arabic, sharia]

of command; so follow it and do not follow the inclinations of those who

are ignorant" (45:18).

Mainstream Islamic exegesis has always interpreted such verses to mean

that Muslims must follow the commandments of Allah as laid out in the

Koran and Hadith—in a word, Sharia.

And Sharia is so concerned with the details of this world, with the

everyday doings of Muslims, that every conceivable human action falls

under five rulings, or ahkam: the forbidden (haram), the

discouraged (makruh), the neutral (mubah), the recommended

(mustahib), and the obligatory (wajib).

Conversely, Islam offers little concerning the spiritual (sidelined

Sufism the exception).

Unlike Christianity, then, Islam without the law—without

Sharia—becomes meaningless. After all, the Arabic word Islam

literally means "submit." Submit to what? Allah's laws as

codified in Sharia and derived from the Koran and Hadith.

The "Islamic reformation" some in the West are hoping for is

really nothing less than an Islam

without Islam—secularization not reformation; Muslims prioritizing

secular, civic, and humanitarian laws over Allah's law; a

"reformation" that would slowly see the religion of Muhammad go

into the dustbin of history.

Such a scenario is certainly more plausible than believing that Islam

can be true to its scriptures in any meaningful way and still peacefully

coexist with, much less complement, modernity the way Christianity does.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment