|

|

Follow the Middle East Forum

|

|

|

|

Related Articles

Nuclear

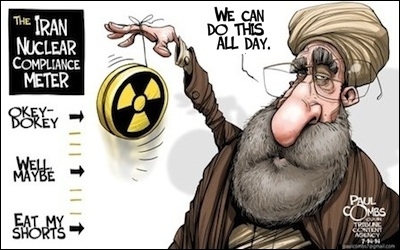

Creepout: Iran's Third Path to the Bomb

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the first of

your friends to like this. Be the first of

your friends to like this.

Originally published under the title, "Creepin': Here's

How Iran Will Really Build the Bomb."

In assessing whether the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) signed by

the P5+1 world powers and Iran last week is an adequate safeguard against

the latter's pursuit of a nuclear weapon, Obama administration officials

and arms control wonks typically discuss two heavily stylized breakout

scenarios.

In an overt breakout, Iran brushes aside nuclear inspectors and begins

openly racing to enrich weapons grade uranium (WGU) using its two

declared enrichment plants at Natanz and Fordow. The JCPOA ostensibly

blocks this path by limiting the number of centrifuges Iran can operate

to 5,060 and capping the amount of low-enriched uranium (LEU) it can keep

on hand to use as feedstock at 300 kilograms. This supposedly lengthens

its breakout time—how quickly it can produce sufficient fissile

material for one atomic bomb should it make a rush to build one—from two

or three months at present to at least a year, giving the international

community more time to mobilize a response to the breakout.

In a covert breakout, or sneakout, Iran builds parallel

infrastructure in secret to produce the fissile material for a bomb. The

JCPOA ostensibly blocks this path with an inspections regime designed to

detect the diversion of fissile material, the construction of illicit

centrifuges, off-the-books uranium mining, and so forth.

The terms of the JCPOA make

small-scale cheating virtually unpunishable.

|

Though much ink has been spilled about whether these two

"paths" to the bomb have been blocked, both presuppose a

decision by Iran to sacrifice its reconciliation with the world in the

next ten to fifteen years for the immediate gratification of building a

weapon (the purpose of a covert breakout is less to avoid detection

before crossing the finish line than to make the process less vulnerable

to decisive disruption).

Such an abrupt change of heart by the Iranian regime is certainly

possible, but more worrisome is the prospect that Iran's nuclear policy

after the agreement goes into effect will be much the same as it was

before—comply with the letter and spirit of its obligations only to the

degree necessary to ward off unacceptably costly consequences. This will

likely take the form of what I call nuclear creepout—activities,

both open and covert, legal and illicit, designed to negate JCPOA

restrictions without triggering costly multilateral reprisals.

The text of the JCPOA appears

designed to give the Iranians wide latitude to interpret their own

obligations.

|

It is important to bear in mind that the JCPOA bars signatories from

re-imposing any sanctions or their equivalents on Iran, except by way of

a United Nations Security Council resolution restoring sanctions.

"That means there will be no punishments for anything less than a

capital crime," explains Robert Satloff. The language demanded by

Iranian negotiators, and accepted by the Obama administration, makes

small-scale cheating virtually unpunishable.

Moreover, the specific terms of the JCPOA appear to have been designed

to give the Iranians wide latitude to interpret their own obligations.

Two, in particular, should raise eyebrows.

The LEU Cap

About 1,000 kilograms of LEU is supposedly needed to produce, through

further enrichment, enough weapons grade uranium for a nuclear explosive

device (let's assume for sake of argument that that the Obama

administration's erroneous math is correct). This is what inspectors

call a "significant quantity" (SQ). The JCPOA's requirement

that Iran "keep its uranium stockpile under 300 kilograms" would

force it to enrich a substantial quantity of natural uranium all the way

up to weapons grade, thereby lengthening the process of producing a SQ by

several months.

|

Iran

is allowed to operate 5,060 IR-1 centrifuges under the terms of the

JCPOA.

|

But what exactly happens to LEU produced by Iranian centrifuges in

excess of the 300-kilogram limit? The JCPOA appendix says it "will be down blended to natural

uranium level or be sold on the international market and delivered to the

international buyer." Maintenance of the 300 kilogram limit relies

upon Iran continually and punctually reprocessing or transferring

material it already possesses.

What happens if Iran's handling of all this is less than perfect?

Suppose 100 kilograms or so of LEU in the process of being down-blended

or delivered to an "international buyer" of Iran's choosing

routinely remains recoverable at any one time because of apparent

inefficiencies and bottlenecks. Would the international community be

willing to cancel the JCPOA over this infraction? Almost certainly not.

What if this number swelled periodically to 150 or 200 kilograms every

so often because of some special complication or another, like a breakout

of plant machinery or truck drivers' strike? Probably not. Since an overt

breakout attempt would likely commence at one of these peaks in LEU

availability (and when smaller amounts of medium enriched uranium have

yet to be converted or transferred), we can knock a month or so off its

breakout time.

The Centrifuges Cap

The Obama administration's one-year breakout time calculation assumes

that Iran uses only the 5,060 IR-1 centrifuges it is allowed to have

spinning under the JCPOA—and that it does not bring more into operation

for a whole year after kicking out inspectors and beginning a sprint for

a nuke. This could have been achieved by dismantling the large majority

of its roughly 15,000 excess centrifuges falling outside this quota, but

Iran insisted from the beginning that it would never destroy any

of them and its adversaries eventually caved.

Although U.S negotiators reportedly proposed a variety of disablement mechanisms

designed to slow down the process of reconnecting them, all were rejected

by the Iranians and the final agreement makes no mention of any. The

JCPOA requires only that excess centrifuges and associated equipment at

Natanz be disconnected and put into IAEA-monitored storage on-site.

At the Fordow facility, buried deep underground, Iran is allowed to keep

"no more than 1044 IR-1 centrifuge machines at one wing"

installed, but not enriching uranium.

There is considerable disagreement among informed analysts about how

long it would take the Iranians to get an appreciable number of these

excess machines up and running, with estimates ranging from a few to

several months. Whatever that length of time is, the Iranians can surely

shorten it by training personnel to rapidly reactivate centrifuge

cascades, modernizing equipment, acquiring new technology, and other

methods not explicitly barred by the JCPOA.

The real danger is that the

mullahs will put off a breakout attempt while creeping out of their

vaguely worded obligations.

|

Indeed, the JCPOA appears to have been drafted by diplomats who failed to imagine that the Iranians might seek to

bolster their latent nuclear weapons capacity under the new rules of the

game with as much guile and gusto as they did under the old. Considering

that the Obama administration's one-year projected breakout time for Iran

is deeply flawed to begin with, Iranian exploitation of

these loopholes could bring it perilously close to the finish line even

while remaining officially in compliance with the JCPOA. If the

international community has less time to respond to a breakout attempt,

an attempt presumably becomes more likely.

But the real danger is that the mullahs will put off a breakout

attempt in the next decade or so, while creeping out of their vaguely

worded obligations. With so many opportunities to escape the strictures

of the JCPOA, the mullahs would be fools not to offer the minimal degree

of compliance necessary to keep it in force (while continually stretching

the boundaries of how minimal that degree can be). Openly exploiting the

JCPOA's loopholes while enjoying its rewards will do more to intimidate

Iran's regional rivals than a reckless dash for the end zone or a

high-risk covert attempt, while paving the way for eventual grudging

international acquiescence to the Islamic Republic's construction of a

bomb.

Gary C. Gambill is a research

fellow at the Middle East Forum.

|

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment