|

|

Follow the Middle East Forum

|

|

|

|

Related Articles

Cheap

Oil Puts the House of Saud at Risk

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the first of

your friends to like this. Be the first of

your friends to like this.

|

Saudi

royal guards stand on duty in front of portraits of King Abdullah bin

Abdulaziz (right), Crown Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz (center), and

second deputy Prime Minister Muqrin bin Abdulaziz.

|

Saudi Arabia spends money like there's no tomorrow. A new report from

the International

Monetary Fund suggests that there might not be a tomorrow for the

House of Saud. Without massive spending cuts, the Kingdom will exhaust

its monetary reserves in five years at current oil prices, the IMF

reckons. Saudi Arabia is a rich country full of poor people, and the

House of Saud has bought a lot of legitimacy by subsidizing its subjects.

The dynasty might not survive the sort of austerity measures that the IMF

insists are necessary to keep the Kingdom from running out of reserves by

2020. Egypt, now dependent on Saudi subsidies, also is at risk.

Gaming the fall of the House of Saud has been a fool's pastime for

years. As William

Quandt wrote in Foreign Affairs twenty years ago, "There

is a cottage industry forming to predict the impending fall of the House

of Saud." Countless experts claimed to see handwriting on the royal

palace wall, but to no avail. Thus far the wily Saudis managed to co-opt,

buy off, or butcher the competition. This time is different. As IHS-Janes

analyst Meda

al Rowas observed last July, Saudi Arabia's clerical establishment is

one of the most important stabilizing mechanisms in the kingdom. Salafist

Wahhabi ideology requires obedience to the confirmed ruler, which in

Saudi Arabia's case, is the king, but only so long as he enforces

Islam."

The Saudi monarchy's survival

tools require a great deal of money.

|

This time may be different. All of the monarchy's survival tools

require a great deal of money, and the challenge to the self-styled

guardians of Islamic purity from the battlefields around the kingdom

gains credibility as Islam sinks deeper into chaos and crisis.

As IHS-Janes analyst Meda

al Rowas observed last July, Saudi Arabia's clerical establishment is

one of the most important stabilizing mechanisms in the kingdom. Salafist

Wahhabi ideology requires obedience to the confirmed ruler, which in

Saudi Arabia's case, is the king, but only so long as he enforces

Islam." The Saudi royal house allied with Egypt's military against the

Muslim Brotherhood, a form of Islamism more attractive to young Saudis

excluded from power and privilege by the monarchy, and ISIS is now

pressing its claim to lead Islam against the sclerotic House of Saud, a

risk noted by numerous

Western analysts. In November 2014 ISIS chief Abu

Bakr al-Baghdadi called on Muslims to rebel against the Saudi

monarchy. ISIS staged

suicide bombings against the country's Shia minority earlier this

year to assert its authority against the government-allied clerical

establishment, and a devastating attack against a Shia

mosque in Kuwait last June.

The royal family has responded to the Islamist threat by styling

itself the Sunni champion against Iran. IHS' al Rowas warns, "King

Salman's attempts to keep the clerical establishment onside, including

allowing the adoption of highly charged sectarian language targeting Iran

and the Shia more generally, risk backfiring in the three-to-five year

outlook, particularly if Saudis believe that the Al-Saud monarchy is

failing to curtail expanding Iranian influence."

In the background to the sectarian war, though, Saudi Arabia's

economic problems present the gravest threat to regime continuity. The

2,000 Saudi princes who control the country subsidize between a quarter

and third of the Saudi population. They may no longer be able to buy

social peace, according to the IMF.

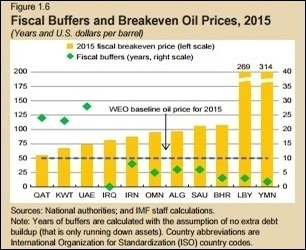

The chart at right shows the oil price at which all the major Middle

Eastern producers can balance their government budgets; in the Saudi

case, the break-even oil price (yellow columns) is $105. The green dots

show the number of years each country has before it runs out of monetary

reserves. Iraq is flat broke now. Saudi and Algeria have five years, and

Iran has eight.

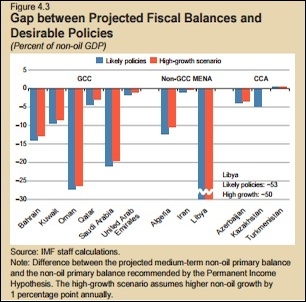

The IMF wants the Saudis to cut the spending equivalent to more than

20% of non-oil GDP, as shown in the IMF's chart below left.

It's not clear whether Saudi Arabia can cut spending so deeply and

maintain political stability. There is no official data on poverty in

Saudi Arabia, but one

Saudi newspaper used social service data to estimate that 6 million

of the kingdom's 20 million inhabitants are poor, some desperately so.

After the 2011 "Arab Spring" disturbances, Riyadh increased

social spending by $37 billion–or $6,000 for every poor person in the

kingdom–in order to preempt the spread of discontent to its own

territory. Saudi Arabia now spends $48.5 billion on defense, according to

IHS, and plans to increase the total to $63 billion by 2020. The monarchy

has to match Iran's coming conventional military buildup after the P5+1

nuclear agreement to maintain credibility.

Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States also keep Egypt afloat. They

pledged $12.5 billion in new aid to Egypt earlier this year, and Egyptian

media project the total aid package at more than $20 billion. Muslim Brotherhood

leader Mohammed Morsi was overthrown in July 2013 as Egypt's economy

collapsed, and his successor Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi immediately

secured help from the Gulf States. Egypt's economy is still

deteriorating. The country's trade balance has widened steadily since the

2011 overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak. The largest Arab country

imports half its food, and buys nearly $40 billion more than it sells.

If the Gulf State subsidy disappears, Egypt's economy will fail.

Offsetting revenues from tourism have fallen sharply, down 41% from 2012

to 2013 to only $5.9 billion a year. Half of Egyptians depend on

government subsidies, which have ballooned the budget deficit to 12.5% of

GDP.

Even under adverse strategic and economic conditions, the House of

Saud would have formidable resources. Its 100,000 man National Guard is

mainly a militarized internal police force staffed by tribal personnel

loyal to the royal family. The Saudis and other Gulf monarchies also hire

Pakistani

mercenaries, who by some estimates comprise a tenth of the 500,000

military and policy employed by the Gulf states. Under some conditions

the large foreign contingent in the Saudi armed forces could become a

danger, e.g., in a revolt by some of the kingdom's 1.5 million Pakistani

workers.

The trouble is that the House of Saud has few friends. It was

abandoned by the United States, its principle ally, in the nuclear deal

with Iran. Russia has aligned with Iran in Syria, with Chinese support.

Turkey was never a friend, and is closer to the Muslim Brotherhood–still

the main opposition to the Saudi monarchy–than it is to the royal family.

In order to appease Wahhabi

clerics, the monarchy has allowed its citizens to finance radical

Islamist causes.

|

In order to keep the favor of the Wahhabi clerical establishment, the

monarchy has allowed wealthy Saudis to provide free-lance financing for

Islamist causes that Riyadh officially rejects. A Chinese official told

me recently that the one thing China fears in the Middle East is Saudi

Arabia, which is funding Wahhabist madrassahs in China's Muslim-majority

Western state of Xinjiang. On the surface, Saudi-Chinese relations are

excellent. China is Riyadh's biggest customer for oil, although China for

the first time bought more

oil from Russia than from Saudi Arabia in 2015. Russia is taking

payment for oil in Chinese currency, while the Saudis demand US dollars.

The trouble is that the central government in Riyadh is either unable

to stop individual Saudis from supporting radical groups, or it is so

beholden to the Wahhabist clerical establishment that is has to

double-deal. Muslim separatism is an urgent Chinese concern. Like Russia,

China doesn't see Iran as a threat; Chinese Muslims are Sunni not Shia).

The spread of Islamic fundamentalism from Saudi-funded madrassahs

frightens China–it has no natural defenses against foreign religious

ideologies on its own soil–and Saudi Arabia is looking more and more like

a liability.

The Saudis are learning that money can't buy strategic preeminence,

just at the point where money threatens to become scarce. The monarchy

has made fools of its doomsayers for decades, but it now may have passed

its best-used-by-date.

David P. Goldman is a senior

fellow at the London Center for Policy Research and the Wax Family Fellow

at the Middle East Forum.

|

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment