|

|

Follow the Middle East Forum

|

Obama Misses the

Mark on Iranian Anti-Semitism

The President himself, apparently stung by criticism

that his approach to Iran is facilitating rather than preventing its path to

the bomb and that he bears primary responsibility for the tensions in

American-Israeli relations, initiated this discussion when he recently gave

an extensive interview to Atlantic magazine

journalist Jeffrey Goldberg on May 21. Then, on May 22, the President spoke

at Adas Israel, a Conservative Washington, D.C. synagogue whose congregants

include many of the city's politics and policy leaders. There, the President spoke of "unbreakable bonds" and a

"friendship that cannot be broken" between the United States and

Israel. He said he was "interested in a deal that blocks every single

one of Iran's pathways to a nuclear weapon — every single path." The

President eloquently recalled the role American Jews played in the Civil

Rights Movement and spoke of "the values we share."

A week later, foreign policy analyst Michael Doran,

whose excellent commentary about Iran I have discussed previously in this blog, wrote a "Letter to My Liberal Jewish

Friends" in which he argued that the existence of shared values, though

important, was not the key issue. It was, instead, the necessary criticism of Obama's policies towards Iran's

nuclear program.

In the interview with Jeffrey Goldberg, the President finally laid out in

public for the first time his view of the role of anti-Semitism in the

government in Tehran. As a historian who has written a great deal about

anti-Semitism, I welcome this terribly belated public discussion of

anti-Semitism in the American foreign policy world. A year ago almost to the

day, on June 2, 2014, I published "Taking Iran's Anti-Semitism Seriously" in the American

Interest magazine. Adam Garfinkle, that journal's fine editor, combines

an insider's grasp of US foreign relations with an understanding of the

nature of anti-Semitism, which he discussed in an essay in 2012. In my essay, I wrote:

The scholarship on the

history of anti-Semitism hasn't yet had a significant impact on the policy

discussions in Washington about Iran. Perhaps too many of our policymakers,

politicians, and analysts still labor under the mistaken idea that radical

anti-Semitism is merely another form of prejudice or, worse, an

understandable (and hence excusable?) response to the conflict between

Israel, the Arab states, and the Palestinians. In fact it is something far

more dangerous, and far less compatible with a system of nuclear deterrence,

which assumes that all parties place a premium on their own survival. Iran's

radical anti-Semitism is not in the slightest bit rational; it is a paranoid

conspiracy theory that proposes to make sense (or rather nonsense) of the

world by claiming that the powerful and evil "Jew" is the driving

force in global politics. Leaders who attribute enormous evil and power to

the 13 million Jews in the world and to a tiny Middle Eastern state with

about eight million citizens have demonstrated that they don't have a suitable

disposition for playing nuclear chess."

On April 6 I returned to these themes in this blog:

"The Iran Deal and Anti-Semitism." Here I expressed

concern about Obama's reference to "the practical streak" in the

Iranian government. So I was very pleased to see that Goldberg had decided to

raise precisely this issue in his now much-discussed—within some

circles–interview with the President. Goldberg thought it was difficult to

negotiate with people who are "captive to a conspiratorial anti-Semitic

worldview not because they hold offensive views, but" in his words

"because they hold ridiculous views." Obama responded as follows:

Well the fact that you

are anti-Semitic, or racist, doesn't preclude you from being interested in

survival. It doesn't preclude you from being rational about the need to keep

your economy afloat; it doesn't preclude you from making strategic decisions

about how you stay in power; and so the fact that the supreme leader is

anti-Semitic doesn't mean that this overrides all of his other

considerations."

In reply to Goldberg's oblique comment that

anti-Semitic European leaders had made irrational decisions, Obama stated:

They may make

irrational decisions with respect to discrimination, with respect to trying

to use anti-Semitic rhetoric as an organizing tool. At the margins, where the

costs are low, they may pursue policies based on hatred as opposed to

self-interest. But the costs here are not low, and what we've been very clear

[about] to the Iranian regime over the past six years is that we will

continue to ratchet up the costs, not simply for their anti-Semitism, but

also for whatever expansionist ambitions they may have. That's what the

sanctions represent. That's what the military option I've made clear I

preserve represents. And so I think it is not at all contradictory to say

that there are deep strains of anti-Semitism in the core regime, but that

they also are interested in maintaining power, having some semblance of

legitimacy inside their own country, which requires that they get themselves

out of what is a deep economic rut that we've put them in, and on that basis

they are then willing and prepared potentially to strike an agreement on their

nuclear program."

Because Goldberg spoke vaguely about "European

leaders," the President either did not have to or did not choose that

moment to speak about his understanding of the role of anti-Semitism in the

Nazi regime and during the Holocaust. That is unfortunate, because it

seems—to this historian at least—that his grasp of the subject leaves

something to be desired.

The consensus among the numerous scholars who have

worked on the subject is that for the Nazis, anti-Semitism was not primarily

a form of discrimination or an organizing tool. It was an ideology that

justified mass murder and did so not for the ulterior purpose of organizing

others but because they believed that exterminating the Jews in the world

would save Germany from destruction and eliminate the primary source of evil

in the world. The extermination was carried out for the sake of these

beliefs. Nor was this ideology at the margins of Nazi policy; it was at its

center.

The President's comments to Goldberg raise questions

about whether the President fully or accurately understands the link between

ideology and policy during the Holocaust. As I wrote in The Jewish Enemy,

the Nazi leadership interpreted the entire Second World War through the prism

of anti-Semitic paranoia in such a way as to interpret the war as one,

incredibly, launched by "world Jewry" to exterminate the German

people. Anti-Semitism then was a key interpretive framework that the Nazis

employed to misunderstand the political realities of the time. If the

President understands this dimension of anti-Semitism it was not evident in

his interview with Goldberg.

Of course, Nazi Germany is gone and Hitler is dead.

So a policy question facing any President of the United States now and in

years to come remains the following: What is the place and the nature of

anti-Semitism in the Iranian regime, and what impact does this ideology have

on its foreign and military policy toward the United States and its allies,

including Israel?

For the first time in his six years in office, the

President publicly acknowledged what scholarly observers of Iran, such as Tel

Aviv University's Meir

Litvak, among others, have pointed out for the past two decades, namely

that indeed "there are deep strains of anti-Semitism in the core

regime." Aside from the obvious rejections of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's

Holocaust-denial circus, this may have been the first time that any official

of the United States government during the Obama years has said anything

remotely approaching the President's remark about "deep strains...in the

core regime." On the contrary, during this era of euphemism, even

pointing to the regime's radical anti-Semitism could raise suspicions of

"Islamophobia."

So President Obama's long-overdue acknowledgment of

what has been obvious to informed observers for decades is most welcome. Yet,

in the same sentence in which he acknowledged this inconvenient truth, he

suggested that the ideological imperative would give way to practical and

rational interests in maintaining power. In so doing, he diminishes the

impact of the ayatollahs' radical anti-Semitism on the whole spectrum of

Iran's foreign and military policy.

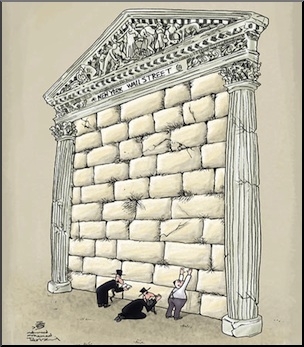

On May 25, two of the President's most astute critics

who write regularly on foreign affairs in widely-read venues took up the

issue of his understanding of anti-Semitism in the Iranian regime. The Wall

Street Journal's Bret Stephens published a column entitled "The Rational Ayatollah Hypothesis," in which he

asked what self-interest drove a regime to deny the Holocaust or how it could

"shore up its domestic legitimacy by preaching a state ideology that

makes the country a global pariah?" He rightly pointed out that

"the Jew-hatred of the Iranian regime is of the cosmic variety: Jews, or

Zionists, [are] the agents of everything that is wrong in this world, from

poverty and drug addiction to conflict and genocide. If Zionism is the root

of evil, then anti-Zionism is the greatest good—a cause to which one might be

prepared to sacrifice a great deal, up to and including one's own life."

And Walter Russell Mead, an editor-at-large of the American Interest

magazine, posted "Obama, Iran and Anti-Semitism," in which he wrote:

There are many forms

of prejudice and bigotry, and they are all twisted and ugly, but Jew hatred

may well be the most damaging to the hater's ability to understand the world.

Jew hatred takes the form of a belief that conspiratorial groups of

super-empowered Jews run the world in secret, cleverly manipulating the news

media and the intelligentsia to hide the truth of their control. Someone who

really believes this isn't just a heart-blighted ignorant boor; someone who

believes this, lives in a house of mirrors, incapable of understanding the

way the world actually works.

For Stephens, Mead, and historically informed

contemporary observers, the radical anti-Semitism that lies at the core of

the Iranian regime is not primarily or only a prejudice or, to use the more

common term, a kind of racism that rests on distorted and false pejorative

views of Jews. Rather, the ayatollahs' anti-Semitism is of the radical sort

that in the past led both to an absurdly irrational yet deadly

misunderstanding of world realities and to the Holocaust. It is an

anti-Semitism that, in Saul Friedlander's terms, produced the era of

extermination following an era of persecution. The views the President

offered to Jeffrey Goldberg indicate either that he does not understand the

nature of radical anti-Semitism, or does not believe that the ayatollahs are

sincere in what they have written and said since Khomeini's exile writings in

the 1970s and the assertions that he and his and his successors have repeated

since coming to power in 1979. He appears to assume a moderation and

pragmatism in Tehran that is belied both by that regime's core beliefs and

its actions.

The policy implications of these differing

understandings of Iran's anti-Semitism are profound. If anti-Semitism is a

form or prejudice and an organizing tool that allows for the kind of

rationality we have witnessed in other nuclear powers such as the Soviet

Union and China, then a policy of containment and deterrence of a nuclear

Iran makes a certain sense. Michael Doran has made a cogent argument that

this is, in fact, the policy that the Obama administration is pursuing. If,

on the other hand, the anti-Semitism of the Iranian regime shares the

qualities of irrationality that we historians of the Holocaust have

documented in Nazi Germany, then a policy of prevention or preemption is

essential because nothing could be worse than an Iran with nuclear weapons.

As I have written before this is not a matter of a left and right. It is

matter of how seriously one takes the Iranians at their word and how one

assesses the connection between ideology and policy in this instance.

Although President Obama's grasp of the history of

anti-Semitism may be imperfect, his recent remarks signal an important shift

in Washington: At last, the discussion of the nature and meaning of radical

anti-Semitism has moved from the world of scholarship into the public debate

about US foreign policy. The Iranian leaders may still insist on conditions

that are so untenable that the President will be unable to present a deal to

Congress by June 30th. If a deal does emerge, Congress will then have thirty

days to examine and debate the agreement. Should that occur, I hope that the

members of Congress will raise the issue of Iran's anti-Semitism not only as

a form of prejudice but as a fundamentally irrational world view that is

incompatible with a system of containment and deterrence. In preparation for

that debate, the various members of the foreign policy scene in and out of

government, in the think tanks and in the media, would be well advised to

spend these early summer weeks reading the books and essays that we

historians have written about the longest hatred as well as the above

mentioned essays by journalists and policy analysts in order to gain an

accurate understanding of its current manifestation in Teheran.

Jeffrey Herf is a professor of

History at the University of Maryland-College Park and a fellow at the Middle

East Forum. His recent works include: Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World (2009) and

The Jewish Enemy: Nazi Propaganda during World War II and the Holocaust

(2006). |

||||||||

|

To subscribe to the MEF mailing lists, go to http://www.meforum.org/list_subscribe.php |

No comments:

Post a Comment