|

Related Articles

The

'Radicalization' Fraud

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the first of

your friends to like this. Be the first of

your friends to like this.

Originally published under the title "The Politics of

Radicalization."

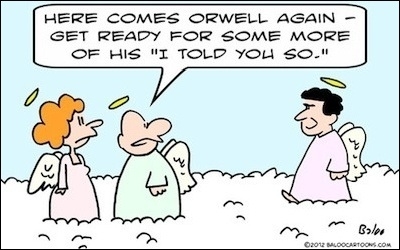

Towards the end of his too-brief life, George Orwell came to the

conclusion that English society had become decadent and that "the

English language is in a bad way." It was 1946, several years before

introducing the world to "newspeak" with his greatest novel, 1984,

when he wrote

perhaps his greatest essay, "Politics and the English

Language," describing the disease he observed and prescribing its

cure.

The belief that "political chaos is connected with the decay of

language" led him to conclude that language had become "ugly

and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish [and] the slovenliness of

our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts."

Today, the ways we speak and write about the threat of Islamism are often

inaccurate and slovenly, making "foolish thoughts" almost inevitable.

Everyone involved needs Orwell's prescription.

The post-9/11 era is rife with what Orwell called "the abuse of

language" ("war on terror," "overseas contingency

operations"), but no abuse more obviously illustrates his complaints

than the media cliché describing how a moderate Muslim becomes an

Islamist: he becomes radicalized. This euphemism (a passive

construction in grammatical terminology) denotes almost nothing. Orwell

calls it a "verbal false limb," that is, a device used to

"save the trouble of picking out appropriate verbs and nouns."

It has become the default explanation for a phenomenon few want to

discuss.

The post-9/11 era is rife with

what Orwell called 'the abuse of language.'

|

"Politics and the English Language" has advice for arresting

the English language's slide into decadence, culminating in 6 rules that

"will cover most cases." Each rule points to its author's zeal

for clear and precise prose, unmarred by clichés, jargon and anything

extraneous. Among the obstacles to clarity, the passive construction is

so severe that rule #4 is "Never use the passive where you can use

the active."

An active structure emphasizes the agent of activity conveyed in the

verb: "Tom kicked the ball." A passive structure

emphasizes the object being acted upon: "The ball was kicked

by Tom." It can also eliminate the agent altogether: "The

ball was kicked." Aside from being imprecise, passive

constructions allow writers to conceal important evidence: who kicked the

ball? Or, more germane to political prose: who dropped the bomb? Who gave

the order? Who planned the attack?

There is much to dislike about both the passive "was

radicalized" construction and the term "radicalization,"

which comes from an adjective (radical) turned into a verb (radicalize)

and then into a noun. The term "self-radicalized," which

appears to be a reflexive passive verb, if such a thing exists, is even

worse.

Consider the following sentences, which could have been pulled from a

thousand sources:

- Tamerlan Tsarnaev

was radicalized in Dagestan.

- Sayed Rizwan

Farook became radicalized by his wife.

- Maj. Malik Nidal

Hasan was self-radicalized.

The passive construction in each blurs the relationship between agent

(Tsarnaev, Farook, Nidal) and the already-vague verb

"radicalized." Each deflects responsibility elsewhere, or omits

it altogether, treating "radicalism" as a contagion that

infects its host upon first contact.

Observing Rule #4 from "Politics and the English Language"

might yield instead the following sentences:

- Tamerlan Tsarnaev

sharpened his nascent hatred for the US among the Islamists in

Dagestan.

- Sayed Rizwan

Farook traveled to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia seeking a wife who

shared his Islamist views.

- Maj. Malik Nidal

Hasan sought spiritual and operational guidance from AQAP leader

Anwar al-Awlaki.

What Gore Vidal called

"the popular Fu Manchu theory that a single whiff of opium will

enslave the mind" is not a good metaphor for Islamism. Islamism is

inculcated over time. Teachers

spread it in schools

with books.

Imams

and community

leaders reinforce it in mosques and

Islamic centers. Some communities

ignore it, and some families

tolerate

it. Sudden

Jihad Syndrome only appears sudden to outsiders.

What Gore Vidal called 'the popular

Fu Manchu theory that a single whiff of opium will enslave the mind'

isn't a good metaphor for Islamism.

|

Orwell insisted that language always be used "as an instrument

for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought," but he

understood that not everyone shared his view.

The "was radicalized" construction has become ubiquitous

mostly by thoughtless repetition, but to those who deliberately

obfuscate, this seemingly inoffensive passive construction provides a way

to avoid what has increasingly become the un-nameable. Maajid Nawaz calls

this "the Voldemort effect: the refusal to call Islamism by its

proper name."

Those who make and influence US counterterrorism policy must recognize

that jihadists are not created accidentally or spontaneously. Speaking

and writing as though they are, either deliberately or through "the

slovenliness of our language," hinders clear thinking. And as Orwell

put it, "to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political

regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and

is not the exclusive concern of professional writers."

A.J. Caschetta is a senior lecturer at the Rochester

Institute of Technology and a Shillman-Ginsburg fellow at the Middle East

Forum.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment