|

Related Articles

Israel's

Challenges in the Eastern Mediterranean

by Efraim Inbar

Middle East Quarterly

Fall 2014 (view PDF)

Be the first of

your friends to like this. Be the first of

your friends to like this.

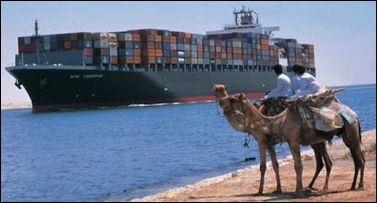

About 90 percent of Israel's foreign trade is carried out

via the Mediterranean Sea. The East Mediterranean is also important in

terms of energy transit. Close to 5 percent of global oil supply and 15

percent of global liquefied natural gas travels via the Suez Canal

while Turkey hosts close to 6 percent of the global oil trade via the

Bosporus Straits and two international pipelines.

|

About 90 percent of Israel's foreign trade is carried out via the

Mediterranean Sea, making freedom of navigation in this area critical for

the Jewish state's economic well-being. Moreover, the newly found gas

fields offshore could transform Israel into an energy independent country

and a significant exporter of gas, yet these developments are tied to its

ability to secure free maritime passage and to defend the discovered

hydrocarbon fields. While the recent regional turmoil has improved

Israel's strategic environment by weakening its Arab foes, the East

Mediterranean has become more problematic due to an increased Russian presence,

Turkish activism, the potential for more terrorism and conflict over

energy, and the advent of a Cypriot-Greek-Israeli axis. The erosion of

the state order around the Mediterranean also brings to the fore Islamist

forces with a clear anti-Western agenda, thus adding a civilizational

dimension to the discord.[1]

The East

Mediterranean Region

The East Mediterranean is located east of the 20o meridian

and includes the littoral states of Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon,

Israel, Gaza (a de facto independent political unit), Egypt, Libya, and

divided Cyprus. The region, which saw significant superpower competition

during the Cold War, still has strategic significance. Indeed, the East

Mediterranean is an arena from which it is possible to project force into

the Middle East. Important East-West routes such as the Silk Road and the

Suez Canal (the avenue to the Persian Gulf and India) are situated there.

In addition, the sources for important international issues such as

radical Islam, international terrorism and nuclear proliferation are

embedded in its regional politics.

Turkish

policy, fueled by Ottoman and Islamist impulses, has led to strains in

the relationship with Israel.

|

The East Mediterranean is also important in terms of energy transit.

Close to 5 percent of global oil supply and 15 percent of global

liquefied natural gas travels via the Suez Canal while Turkey hosts close

to 6 percent of the global oil trade via the Bosporus Straits and two

international pipelines. The discovery of new oil and gas deposits off

the coasts of Israel, Gaza, and Cyprus and potential for additional

discoveries off Syria and Lebanon, is a promising energy development.

Breakdown of

the U.S. Security Architecture

The naval presence of the U.S. Sixth Fleet was unrivalled in the

post-Cold War period, and Washington maintained military and political

dominance in the East Mediterranean.[2] Washington also managed the

region through a web of alliances with regional powers. Most prominent

were two trilateral relationships, which had their origins in the Cold

War: U.S.-Turkey-Israel and U.S.-Egypt-Israel.[3] This security architecture has

broken down.

Hamas leader Ismail Haniya (left) meets with Turkish

president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. With the Islamist Erdoğan at its helm,

Turkey supports Hamas, a Muslim Brotherhood offshoot; helps Iran evade

sanctions; assists Sunni Islamists moving into Syria; propagates

anti-U.S. and anti-Semitic conspiracies while, at home, the regime

displays increasing authoritarianism.

|

In the post-Cold War era, Ankara entered into a strategic partnership

with Jerusalem, encouraged by Washington.[4] The fact that the two strongest

allies of the United States in the East Mediterranean cooperated closely

on strategic and military issues was highly significant for U.S.

interests in the region. Yet, the rise of the Islamist Justice and

Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) since its electoral

victory of November 2002 has led to a reorientation in Turkish foreign

policy which, under the AKP, has distanced itself from the West and

developed ambitions to lead the Muslim world.[5] With Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at

its helm, Turkey supports Hamas, a Muslim Brotherhood offshoot; helps

Iran evade sanctions; assists Sunni Islamists moving into Syria and mulls

an invasion of Syria; propagates anti-U.S. and anti-Semitic conspiracies

while the regime displays increasing authoritarianism at home. Moreover,

Turkey's NATO partnership has become problematic, particularly after a

Chinese firm was contracted to build a long-range air and anti-missile

defense architecture.[6]

Turkish policy, fueled by Ottoman and Islamist impulses, has led to an

activist approach toward the Middle East and also to strains in the

relationship with Israel. This became evident following the May 2010

attempt by a Turkish vessel, the Mavi Marmara, to break the

Israeli naval blockade of Gaza. In October 2010, Turkey's national

security council even identified Israel as one of the country's main

threats in its official policy document, the "Red Book." These

developments fractured one of the foundations upon which U.S. policy has

rested in the East Mediterranean.

Stability in the East Mediterranean also benefited from the

U.S.-Egyptian-Israeli triangle, which began when President Anwar Sadat

decided in the 1970s to switch to a pro-U.S. orientation and subsequently

to make peace with Israel in 1979. Egypt, the largest Arab state, carries

much weight in the East Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Africa.

Sadat's successor, Husni Mubarak, continued the pro-U.S. stance during

the post-Cold War era. The convergence of interests among the United

States, Egypt, and Israel served among other things to maintain the Pax

Americana in the East Mediterranean.

Washington

has offered confused, contradictory, and inconsistent responses to the

Arab uprisings.

|

Yet, the U.S.-Egyptian-Israeli relationship has been under strain

since Mubarak's resignation in February 2011. Egypt's military continued

its cooperation with Israel to maintain the military clauses of the 1979

peace treaty. But the Muslim Brother-hood, which came to power via the

ballot box, was very reserved toward relations with Israel, which the

Brotherhood saw as a theological aberration. Moreover, the Brotherhood

basically held anti-U.S. sentiments, which were muted somewhat by

realpolitik requirements, primarily the unexpected support lent it by the

Obama administration.[7]

The Egyptian army's removal of the Muslim Brotherhood regime in July

2013 further undermined the trilateral relationship since the U.S.

administration regarded the move as an "undemocratic"

development. Washington even partially suspended its assistance to Egypt

in October 2013, causing additional strain in relations with Cairo. This

came on the heels of President Obama's cancellation of the Bright Star

joint military exercise and the Pentagon's withholding of delivery of

weapon systems. The U.S. aid flow has now been tied to "credible

progress toward an inclusive, democratically-elected, civilian government

through free and fair elections."[8] Israeli diplomatic efforts to

convince Washington not to act on its democratic, missionary zeal were

only partially successful.[9] These developments have

hampered potential for useful cooperation between Cairo, Jerusalem, and

Washington.

The turbulence in the Arab world since 2011 has also underscored the

erosion in the U.S. position. This is partly due to the foreign policy of

the Obama administration that can be characterized as a deliberate,

"multilateral retrenchment … designed to curtail the United States'

overseas commitments, restore its standing in the world, and shift

burdens onto global partners."[10] It is also partly due to

Washington's confused, contradictory, and inconsistent responses to the

unfolding events of the Arab uprisings.[11] Furthermore, the ill-conceived

pledge of military action in Syria in response to the use of chemical

weapons by Assad and the subsequent political acrobatics to avoid

following through elicited much ridicule.[12]

This was followed by the November 2013 nuclear deal, hammered out

between U.S.-led P5+1 group and Iran, that allows the Islamic Republic to

continue enriching uranium as well as weaponization and missiles—the

delivery systems—that has been viewed in the East Mediterranean (and elsewhere)

as a great diplomatic victory for Tehran. Regional leaders have seen

Washington retreat from Iraq and Afghanistan, engage (or appease) its

enemies Iran and Syria, and desert friendly rulers. All have strengthened

the general perception of a weak and confused U.S. foreign policy.

North of Israel, along the Mediterranean coast, sits

Lebanon, a state dominated by the radical Shiite Hezbollah. Beirut has

already laid claim to some of the Israeli-found offshore gas fields,

shown above. Moreover, Syria, an enemy of Israel and long-time ally of

Iran, exerts considerable influence in Lebanon.

|

Drained by the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and blessed with new

energy finds, Washington does not want to get dragged into additional

conflicts in a Middle East that no longer seems central to its interests.

As it edges toward energy independence, Washington is apparently losing

interest in the East Mediterranean and the adjacent Middle East. This

parallels Obama's November 2011 announcement of the "rebalance to

Asia" policy.[13]

The rise of China is an understandable strategic reason for the

reinforcement of U.S. military presence in Asia. While little has been

done to implement the Asia pivot, cuts in the U.S. defense budget clearly

indicate that such a priority will be at the expense of Washington's

presence elsewhere, including the East Mediterranean. The U.S. naval

presence in the Mediterranean dwindled after the end of the Cold War and

the mounting needs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.[14] At the height of the Cold War,

the Sixth Fleet regularly comprised one or two aircraft carrier task

forces; today it consists of a command ship and smaller vessels such as

destroyers. While the U.S. military is still capable of acting in the

East Mediterranean, the general perception in the region is that the

Obama administration lacks the political will and skills to do so.

The possibility that European allies in NATO or the European Union

will fill the U.S. position in the East Mediterranean is not taken seriously.

Europe is not a real strategic actor since it lacks the necessary

military assets, a clear strategic vision, as well as the political will

to take up the U.S. role. Others, such as Russia, which has long

maintained a base in Syria, might.

Growing

Islamist Presence

Elements of radical Islam are increasingly powerful around the East

Mediterranean basin. The Muslim-majority countries have difficulties in

sustaining statist structures, allowing for Islamist political forces to

exercise ever-greater influence. Indeed, Islamist tendencies in Libya,

Egypt, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey all threaten the current

unrestricted access to the area by Israel and the West.

The

Egyptian military's grip over the Sinai Peninsula is tenuous. Full

Egyptian sovereignty has not been restored.

|

Libya remains chaotic three years after the uprising against Mu'ammar

al-Qaddafi. Such lack of order may lead to the disintegration of the

state and allow greater freedom of action for Muslim extremists.[15] Libya's eastern neighbor,

Egypt, is now ruled again by the military, but it is premature to

conclude that the Islamist elements will play only a secondary role in

the emerging political system. They still send multitudes into the

streets of Egyptian cities to destabilize the new military regime. Apart

from the important Mediterranean ports, Egypt also controls the Suez

Canal, a critical passageway linking Europe to the Persian Gulf and the

Far East that could fall into the hands of Islamists.

Even if the Egyptian military is able to curtail the Islamist forces

at home, its grip over the Sinai Peninsula is tenuous. Under Gen. Abdel

Fattah al-Sisi, attempts to dislodge the Sunni jihadists roaming Sinai

have increased, but full Egyptian sovereignty has not been restored. This

could lead to the "Somalization" of the peninsula, negatively

affecting the safety of naval trade along the Mediterranean, the

approaches to the Suez Canal, and the Red Sea. Nearby Gaza is currently

controlled by Hamas, a radical Islamist organization allied with Iran.

Containment of the Islamist threat from Gaza remains a serious challenge.

North of Israel, along the Mediterranean coast, sits Lebanon, a state

dominated by the radical Shiite Hezbollah. It has already laid claim to

some of the Israeli-found offshore gas fields. Moreover, Syria, an enemy

of Israel and long-time ally of Iran, exerts considerable influence in

Lebanon. The Assad regime remains in power, but any Syrian successor

regime could be Islamist and anti-Western.

Further on the East Mediterranean coastline is AKP-ruled Turkey. A

combination of Turkish nationalism, neo-Ottoman nostalgia, and

Islamist-jihadist impulses has pushed Ankara away from a pro-Western

foreign orientation toward an aggressive posture on several regional

issues. Turkey is interested in gaining control over the maritime gas

fields in the eastern Mediterranean, which would limit its energy

dependence on Russia and Iran and help fulfill its ambitions to serve as

an energy bridge to the West. This puts Ankara at loggerheads with

Nicosia and Jerusalem, which share an interest in developing the

hydrocarbon fields in their exclusive economic zones and exporting gas to

energy-thirsty Europe. Indeed, Ankara also flexed its naval muscles by

threatening to escort flotillas trying to break the Israeli blockade on

Gaza.

West of Turkey is Greece, a democratic, Western state with a stake in

the protection of the Greek Cypriots from Muslim domination. However, it

has limited military ability to parry the Turkish challenge alone and is

wracked by economic problems. Many East Mediterranean states also would

likely favor the return of Cyprus to Turkish (and Muslim) rule. This

preference introduces a civilizational aspect to the emerging balance of

power.

A New

Strategic Equation

Russian warships arrive at the Syrian port city of Tartus,

January 8, 2014. The Russians have retained a naval base at Tartus and

have gradually increased fleet size and stepped up patrols in the East

Mediterranean, roughly coinciding with the escalation of the Syrian

civil war. Moscow also gained full access to a Cypriot port and recently

announced the establishment of a Mediterranean naval task force

"on a permanent basis."

|

There is now a power vacuum in the East Mediterranean and an uncertain

future. Several developments are noteworthy: a resurgence of Russian

influence, the potential for Turkish aggression, the emergence of an

Israeli-Greek-Cypriot axis, an enhanced terrorist threat, greater Iranian

ability to project power in the region, and the potential for wars over

gas fields.

Russia: The power vacuum makes it easier for Moscow to

recapture some of its lost influence after the end of the Cold War. While

U.S. and European navies in the region have steadily declined for years

as this theater has been considered of diminishing importance, Russia has

retained its Tartus naval base on the Syrian coast and has gradually

improved its fleet size and stepped up patrols in the East Mediterranean,

roughly coinciding with the escalation of the Syrian civil war.[16] Moscow's new military

footprint in the East Mediterranean has been underscored by multiple

Russian naval exercises. During his visit to the Black Sea Fleet in

February 2013, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu stressed that the

"Mediterranean region was the core of all essential dangers to

Russia's national interests" and that continued fallout from the

Arab upheavals increased the importance of the region. Shortly after, he

announced the establishment of a naval task force in the Mediterranean

"on a permanent basis."[17]

Moscow also gained full access to a Cypriot port.[18] A member of the European Union

but not NATO, and painfully aware that the West is not likely to offer a

credible guarantee against potential Turkish aggression, Nicosia has come

to consider Moscow a power able to provide a modicum of deterrence

against Ankara.[19]

Russian diplomacy and material support have also been crucial to

keeping Syria's Bashar al-Assad in power, making Moscow a tacit ally of

Iran.[20]

No less important, Russia has increased its leverage in Egypt—the most

important Arab state—following the military coup. According to many

reports, a large arms deal, to the tune of U.S. $2-3 billion, and naval

services at the port of Alexandria, were discussed between the two

countries at the beginning of 2014. If these deals do indeed materialize,

this would represent an important change in Egyptian policy. It is not

clear whether the Western powers fully understand the strategic

significance of Egypt moving closer to Russia.

Despite its problems with Muslim radicals at home, Moscow has also

maintained good relations with Hamas. In contrast to most of the

international community, which considers Hamas a terrorist organization,

in 2006, the Russian government invited a Hamas delegation to Moscow for

talks.[21]

In 2010, together with Turkey, Russia even called for bringing Hamas into

the diplomatic process attempting to achieve an Israeli-Palestinian

agreement.[22]

Finally, Russia—an energy producer—has shown interest in the newly

Russian

support has been crucial to keeping Syria's Assad in power, making

Moscow a tacit ally of Iran.

|

discovered offshore energy fields.[23] In July 2012, Russian

president Vladimir Putin visited Israel to discuss the gas fields, among

other things. In December 2013, Moscow signed a 25-year energy deal with

Syria that opens the way for its eventual move into the gas-rich East

Mediterranean.[24]

Turkey: The Russian encroachment has been paralleled by

greater Turkish assertiveness. Under certain conditions, Ankara may be

tempted to capitalize on its conventional military superiority to force

issues by military action in several arenas, including the Aegean,

Cyprus, Syria, and, perhaps, Iraq. The potential disintegration of Syria

and the possible establishment of an independent Greater Kurdistan could

be incentives for Turkish intervention. The collapse of the AKP's earlier

foreign policy, dubbed "zero problems" with Turkey's neighbors,

could push Ankara into open confrontation. Aggressive Russian behavior in

Crimea could reinforce such tendencies.

Similarly, Turkey's appetite for energy and aspiration to become an

energy bridge to Europe could lead to aggressive behavior. Turkish

warships have harassed vessels prospecting for oil and gas off Cyprus. [25] Cyprus is also the main

station for a Turkish desired pipeline taking Levant Basin gas to Turkey

for export to Europe. Ankara might even be tempted to complete its

conquest of Cyprus, begun when it invaded and occupied the northern part

of the island in 1974.

Ankara has embarked on military modernization and has ambitious

procurement plans. Turkish naval power is the largest in the East

Mediterranean.[26]

In March 2012, then-navy commander Admiral Murat Bilgel outlined Turkey's

strategic objective "to operate not only in the littorals but also

on the high seas," with high seas referring to the East

Mediterranean. The December 2013 decision to purchase a large 27,500-ton

landing dock vessel capable of transporting multiple tanks, helicopters,

and more than a thousand troops, reflects its desire to project naval

strength in the region.[27]

Israel, Cyprus, and Greece: Turkey's threats and

actions have brought Israel, Cyprus, and Greece closer together. Beyond

blocking a revisionist Turkey and common interests in the area of energy

security, the three states also share apprehensions about the East

Mediterranean becoming an Islamic lake. Athens, Jerusalem, and Nicosia

hope to coordinate the work of their lobbies in Washington to sensitize

the U.S. administration to their concerns. Battling an economic crisis,

Greece wants the new ties with Israel to boost tourism and investment,

particularly in the gas industry, while deepening its military

partnership with a powerful country in the region.[28] Moreover, the emerging

informal Israeli-Greek alliance has the potential to bring Israel closer

to Europe and moderate some of the pro-Palestinian bias occasionally

displayed by the European Union.

Greece's George Papandreou (left) and Benjamin Netanyahu in

Athens, August 2010. Turkey's threats and actions have brought Israel

and Greece closer together . Battling an economic crisis, Greece wants

the new ties with Israel to boost tourism and investment, particularly

in the gas industry, while deepening its military partnership with a

powerful country in the region.

|

Following Benjamin Netanyahu's visit to Greece in August 2010,

cooperation between the two countries has been broad and multifaceted,

covering culture, tourism, and economics. One area of cooperation

discussed was the possibility of creating a gas triangle—Israel-Cyprus-Greece—with

Greece the hub of Israeli and Cypriot gas exports to the rest of Europe.[29] Such a development could

lessen the continent's energy dependence on Russia.[30] Another project that can

further improve the ties between the countries is a proposed undersea

electric power line between Israel, Cyprus, and Greece. Currently Israel

and Cyprus are isolated in terms of electricity and do not export or

import almost any power.

Israeli-Greek military cooperation has already manifested itself in a

series of multinational—Greek, Israel, and United States—joint air and

sea exercises under the names Noble Dina[31] and Blue Flag (which included

an Italian contingent).[32] Greece also cooperated with

Israel in July 2011 by preventing the departure of ships set to sail to

Gaza.[33]

International terrorism: Developments in the Arab states

of the East Mediterranean have increased the threat of international

terrorism. As leaders lose their grip over state territory and borders

become more porous, armed groups and terrorists gain greater freedom of

action. Moreover, security services that dealt with terrorism have been

negatively affected by domestic politics and have lost some of their

efficiency. Sinai has turned into a transit route for Iranian weapons to

Hamas and a base for terrorist attacks against Israel. Hamas has even set

up rocket production lines in Sinai in an effort to protect its assets,

believing Jerusalem would not strike targets inside Egypt for fear of

undermining the bilateral relations.[34] Syria has also become a haven

for many Islamist groups as result of the civil war.

Furthermore, as weakened or failed states lose control over their

security apparatus, national arsenals of conventional and nonconventional

arms have become vulnerable, which may result in the emergence of

increasingly well-armed, politically dissatisfied groups seeking to harm

Israel. For example, following the fall of Qaddafi, Libyan SA-7 anti-air

missiles and anti-tank rocket-propelled grenades reached Hamas in Gaza.[35] Similarly, in the event of a

Syrian regime collapse, Damascus's advanced arsenal, including chemical

weapons, shore-to-ship missiles, air defense systems, and ballistic

missiles of all types could end up in the hands of Hezbollah or other

radical elements.[36]

Salafi jihadist groups have reportedly attacked the Suez

Canal several times. In 2013, an Egyptian court sentenced 26 members of

an alleged terrorist group to death over plans to target ships in the

canal. In 2014, Egyptian authorities again tightened security around

the canal following fears that Muslim Brotherhood supporters of Mohamed

Morsi might attack ships in the waterway in protest over his trial.

|

Finally, terrorist activities could adversely affect the navigation

through the Suez Canal, an important choke point. Salafi jihadist groups

have attacked the canal several times already.[37]

The Iranian presence: The decline in U.S. power, the

timidity of the Europeans, and the turmoil in the Arab world have

facilitated Iranian encroachment of the East Mediterranean. Indeed,

Tehran's attempts to boost its naval presence in the Mediterranean are

part of an ambitious program to build a navy capable of projecting power

far from Iran's borders.[38] Tehran would like to be able

to supply its Mediterranean allies: Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and

Hamas in Gaza. Entering the Mediterranean also enhances Iran's access to

Muslim Balkan states, namely Albania, Bosnia, and Kosovo, giving Tehran a

clear stake in the outcome of the Syrian civil war. Assad's hold on power

is critical for the "Shiite Crescent" from the Persian Gulf to

the Levant, which would enhance Iranian influence in the Middle East and

the East Mediterranean. Tehran has also been strengthening naval

cooperation with Moscow, viewed as a potential partner in efforts to

limit and constrain U.S. influence.[39]

Tehran's

attempts to boost its naval presence in the Mediterranean are part of a

program to build a navy capable of projecting power far from Iran's

borders.

|

Wars over gas fields: The discovery of gas fields in the

East Mediterranean could potentially escalate tensions in this

increasingly volatile region. Competing claims to the gas fields by

Israel's former ally Turkey as well as by its neighbor Lebanon (still in

a de jure state of war) have precipitated a buildup of naval

forces in the Levant basin by a number of states, including Russia.

Israel's wells and the naval presence protecting them also offer new

targets at sea to its longstanding, non-state enemies, Hezbollah and Hamas.

Conscious of these threats, the Israel Defense Forces chief of staff,

Lt. Gen. Benny Gantz, has approved the navy's plan to add four offshore

patrol vessels.[40] Israeli defense circles hope

that Israel's expanding navy, combined with continuous improvement of

land and air assets and increasing cooperation with Greece and Cyprus,

will give pause to any regional actor that would consider turning the

Mediterranean Sea into the next great field of battle. Indeed, the

Israeli navy is now preparing to defend the gas field offshore of Israel.[41]

The future role of Russia in these developments is not clear. Some

analysts believe that Moscow is interested primarily in marketing the

region's energy riches. Securing gas reserves in the East Mediterranean

will also help Moscow safeguard its dominant position as a natural gas

supplier to western Europe, which could be challenged by new competitors

in the region. Yet, delays and disruptions in moving gas to Europe might

further strengthen Russia's role as a major energy supplier to Europe and

keep prices high, which is beneficial for Moscow. Moreover, as the

Ukraine crisis indicated, geopolitics still is a dominant factor in

Russian decision-making.

Conclusion

Stability in the East Mediterranean can no longer be taken for granted

as U.S. forces are retreating. Europe, an impotent international actor,

cannot fill the resulting political vacuum. Russia under Putin is beefing

up its naval presence. Growing Islamist freedom of action is threatening

the region. Turkey, no longer a true ally of the West, has its own

Mediterranean agenda and the military capability to project force to

attain its goals. So far, the growing Russian assertiveness has not

changed the course of Turkish foreign policy. The disruptive potential of

failed states, the access of Iran to Mediterranean waters, and interstate

competition for energy resources are also destabilizing the region. But

it is not clear whether the Western powers, particularly the United

States, are aware of the possibility of losing the eastern part of the

Mediterranean Sea to Russia or radical Islam, or are

preparing in any way to forestall such a scenario. U.S. naiveté and

European gullibility could become extremely costly in strategic terms.

The Israeli perspective on the East Mediterranean region is colored by

its vital need to maintain the freedom of maritime routes for its foreign

trade and to provide security for its newly found gas fields. While its

strategic position has generally improved in the Middle East, Jerusalem

sees deterioration in the environment in the East Mediterranean. A

growing Russian presence and Turkish assertiveness are inimical to

Israel's interests. Developments along the shores of the East Mediterranean

also decrease stability and enhance the likelihood of more Islamist

challenges.

In civilizational terms, the East Mediterranean has served as a point

of contention in the past between Persia and the ancient Greeks and

between the Ottomans and Venetians. It is the location where the struggle

between East and West takes place. After the Cold War, the borders of the

West moved eastward. Now, they could easily move in the other direction.

Efraim Inbar, director of the Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for

Strategic Studies, is professor of political studies at Bar-Ilan

University and a Shilman-Ginsburg Writing Fellow at the Middle East

Forum.

[1] Samuel P.

Huntington, "The Clash of Civilizations?" Foreign Affairs,

Summer 1993, pp. 22-49.

[2] For more,

see Seth Cropsey, Mayday: The Decline of American Naval Supremacy

(New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2013).

[3] Jon B.

Alterman and Haim Malka, "Shifting Eastern Mediterranean

Geometry," The Washington Quarterly, Summer 2012, pp. 111-25.

[4] Efraim

Inbar, The Israeli-Turkish Entente (London: King's College

Mediterranean Program, 2001); Ofra Bengio, The Turkish-Israeli

Relationship. Changing Ties of Middle Eastern Outsiders (New York:

Palgrave, 2004).

[5] Rajan Menon

and S. Enders Wimbush, "The US and Turkey: End of an Alliance?"

Survival, Summer 2007, pp. 129-44; Efraim Inbar,

"Israeli-Turkish Tensions and Their International

Ramifications," Orbis, Winter 2011, pp. 135-9; Ahmet

Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik: Türkiye'nin Uluslararası Konumu

(Istanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2001).

[6] Tarik

Ozuglu, "Turkey's Eroding Commitment to NATO: From Identity to

Interests," The Washington Quarterly, Summer 2012, pp.

153-64; Burak Ege Bekdil, "Allies Intensify Pressure on Turkey over

China Missile Deal," The Defense News, Feb. 24, 2014, p. 8.

[7] Liad Porat,

"The Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace," Mideast

Security and Policy Studies, no. 102, BESA Center for Strategic Studies,

Ramat Gan, Aug. 1, 2013.

[8] Tally

Helfont, "Slashed US Aid to Egypt and the Future of the Bilateral

Relations," Institute for National Strategic Studies, Washington,

D.C., Oct. 13, 2013.

[9] Interview

with senior Israeli official, Jerusalem, Apr. 7, 2013.

[10]

Daniel W. Drezner, "Does Obama Have a Grand Strategy? Why We Need

Doctrines in Uncertain Times," Foreign Affairs, July/Aug. 2011,

p. 58.

[11]

Eitan Gilboa, "The United States and the Arab Spring," in

Efraim Inbar, ed., The Arab Spring, Democracy and Security: Domestic

and Regional Ramifications (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 51-74.

[12] Eyal

Zisser, "The Failure of Washington's Syria Policy," Middle

East Quarterly, Fall 2013, pp. 59-66.

[13] "Pivot to the Pacific?

The Obama Administration's 'Rebalancing' toward Asia," Congressional

Research Service, Washington, D.C., Mar. 28, 2012.

[14] Seth

Cropsey, "All Options Are Not on the Table: A Briefing on the US

Mediterranean Fleet," World Affairs Journal, Mar. 16, 2011;

Steve Cohen, "America's Incredible Shrinking Navy," The Wall

Street Journal, Mar. 20, 2014.

[15] Florence

Gaub, "A Libyan Recipe for Disaster," Survival,

Feb.-Mar. 2014, pp. 101-20.

[16] Thomas

R. Fedyszyn, "The Russian Navy 'Rebalances' to the

Mediterranean," U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, Dec. 2013.

[17] Ibid.

[18]

InCyprus.com, Jan. 11, 2014.

[19]

Interviews with senior officials, Nicosia, Oct. 10, 2012.

[20] Zvi

Magen, "The Russian Fleet in the Mediterranean: Exercise or Military

Operation?" Institute for National Strategic Studies, Washington,

D.C., Jan. 29, 2013.

[21] Igor

Khrestin and John Elliott, "Russia and the Middle East," Middle

East Quarterly, Winter 2007, pp. 21-7.

[22] The

Jerusalem Post, May 12, 2010.

[23] Thane

Gustafson, "Putin's Petroleum Problem," Foreign Affairs,

Nov./Dec. 2012, pp. 83-96.

[24] United

Press International, Jan.

16, 2014.

[25] For example,

see, Gary Lakes, "Oil,

Gas and Energy Security," European Rim Policy and Investment

Council (ERPIC, Larnaca, Cyprus), Oct. 23, 2009.

[26] "Turkey,"

Institute for National Strategic Studies, Washington, D.C., Dec. 24,

2012, pp. 19-25.

[27]The

Jerusalem Post, Feb. 4, 2014.

[28]

Bloomberg News Service (New York), Aug. 2011.

[29] The

Jerusalem Post, Sept. 10, 2013.

[30] Ibid.,

Aug. 2, 2011.

[31] The

Times of Israel (Jerusalem), Mar.

25, 2014.

[32] Arutz

Sheva (Beit El and Petah Tikva), Nov.

25, 2013.

[33]Haaretz

(Tel Aviv), July 2, 2011.

[34] The

Jerusalem Post, Dec.

11, 2011.

[35] Reuters,

Aug.

29, 2011.

[36] Defense

News (Springfield, Va.), Dec. 12, 2011.

[37] USA

Today, Nov. 4, 2013.

[38] Shaul

Shay, "Iran's

New Strategic Horizons at Sea," Arutz Sheva, July 30,

2012; Agence France-Presse, Jan. 17, 2013.

[39] Michael

Eisenstadt and Alon Paz, "Iran's

Evolving Maritime Presence," Policy Watch, no. 2224,

Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, D.C., Mar. 13,

2014.

[40] Israel

Hayom (Tel Aviv), July 10, 2012.

[41] Defense

News (Springfield, Va.), Feb. 27, 2012.

Related

Topics: Israel & Zionism

| Efraim Inbar

| Fall 2014 MEQ

This text may be reposted or forwarded so long as it is

presented as an integral whole with complete and accurate information

provided about its author, date, place of publication, and original URL.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment