After

Surviving Evin Prison, She Works To Free Others

by Abigail R. Esman

Special to IPT News

March 31, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the

first of your friends to like this. Be the

first of your friends to like this.

At an average pace,

most people can cover about three miles if they walk for a full hour. At an average pace,

most people can cover about three miles if they walk for a full hour.

For 105 days in the summer of 2007, Haleh

Esfandiari took such a walk every morning and again each afternoon and

evening, in effect cumulatively walking the distance from New York City to

Nashville. It was how she kept herself sane as she endured solitary

confinement at Evin prison in Tehran, walking in circles, in her cell.

"You despair when you are in solitary confinement," she later recounted in the Wilson Quarterly.

"You don't know what's going on in the outside world. You don't know

whether people are working to get you out. You don't get to see your

lawyer. I coped by concentrating on the monotonous regime I had established

to keep myself from falling apart."

Esfandiari's ordeal began when the then-67-year-old was heading to the

airport, returning home to Washington, D.C. after visiting her 93-year-old

mother in Tehran. A dual Iranian-American and director of the Middle East Program at the non-partisan Wilson

Center, Esfandiari suddenly found herself confronted by a group of

masked bandits who seized her suitcases and both passports and disappeared

into the night.

"At first I thought, 'okay, robberies happen at two in the morning

on the way to the airport. So what?" she recalls now in an interview

over Skype. "But within 24 or 48 hours, I realized this was not your

ordinary robbery." Rather, she'd been held up by government henchmen,

marking the beginning of an eight-month ordeal.

At first, Esfandiari was commanded to appear at the "Office of the

Presidency," a euphemism for Iran's security agency, where she endured lengthy interrogations along with threats and

pressure to identify "networks" of people and organizations the

Iranian government believed were planning a revolution.

Eventually, however, her even-handed, persistent repetition of answers

proved unsatisfactory. Esfandiari was arrested on charges of "working

for an organization that was conspiring to foment a 'velvet revolution in

Iran,'" her husband, Shaul Bakhash, explained in an editorial he wrote during her

incarceration.

For the next 105 days, Esfandiari faced further interrogations, to which

she was brought blindfolded and where she was forced to face the wall for

eight or nine hours at a time. "I had two interrogators," she

tells me. "I never saw either one of them. I could only hear

them." She refused to eat prison food, arranging instead for her

family to provide money to the guards, who shopped for fruits and vegetables

for her to eat instead. She lost 20 pounds. And still, she walked, trying

to memorize her interrogations, planning books that she would write –

anything to hold her mind intact and keep her focus away from her

conditions.

In certain respects, Esfandiari was fortunate. Other women at Evin

prison have faced torture, serial rape, and other abuses. She experienced

none of this, in part, she believes, because of her age, and in part,

perhaps, because Canadian-Iranian photojournalist Zahra Kazemi had been

raped, tortured, and beaten to death at the same prison in 2003. In 2006,

Kazemi's son Stephan filed suit against the Iranian government.

"I think they were scared of another international incident,"

Esfandiari says.

Instead, her captors worked to break her psyche. They told her she'd

been forgotten by the world outside, that no one was working for her

release. They hadn't counted on her resolve, or the strength of her

intellect. "I knew that my husband would do everything possible to get

me out," she says now. "Both of us know how the system works ...

What I didn't know was that the day they arrested me, everybody started

writing about me." She became known as the "67-year-old grandmother

sitting in Evin prison."

And it wasn't only Washington and her family who fought for her release.

"I had worked all my life, ever since I came to the Wilson Center, for

Middle Eastern women," she says. "They now became a voice for

me."

Her August 2007 release came when her captors realized she was not

changing her story. "But it wasn't that they set me free and said,

'okay, sorry for keeping you,'" she explains. "My mother had had

to put up her apartment as bail, and that bail is still not lifted."

In fact, the case remains open today. "They can always summon me

back," she says.

Still, she has kept her Iranian citizenship. "I love Iran,"

she says. "I hope one day I will be able to go back."

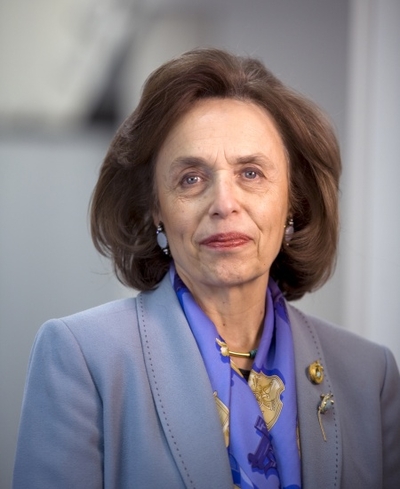

Elegantly coiffed on a Sunday morning, Esfandiari looks younger than her

years. Her work in the United States has earned her the appreciation and

respect not just of other Middle Eastern women, but of many who work for

women's rights and peace in the Middle East: she has received a John and

Catherine D. MacArthur grant, and was among the first recipients of the

Project on Middle East Democracy's "Leader for Democracy" award.

And she clearly hasn't stopped. She wrote tirelessly of Washington

Post reporter Jason Rezaian's incarceration for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and others. She

continues to work at the Wilson Center. She continues, too, to fight for

justice in Iran and the horrific plight of its political prisoners at Evin.

"Evin has always been very bad, from day one," she observes.

"It's been like a pendulum: it's bad, it's less bad, it becomes a bit

somehow less bad, then moves again to bad. It varies from person to person

and the political situation in Iran: whenever the government feels

insecure, conditions in prison get bad. When they are more secure, they

arrange furlough for political prisoners perhaps, phone calls, visits with

family. It changes." But in the end, life for the prisoners of Evin

remain always inhuman, and inhumane.

Is there anything Westerners can do to change the situation?

Esfandiari offers limited hope. International pressure does work to help

free dual nationals, she says. Articles in the press, like those about

Jason Rezaian, can be surprisingly effective.

"So to keep quiet is not right," she says. "To expose the

situation makes a big difference. There is something about advocacy, when

you are in prison, when you are in solitary confinement, when you are at

the mercy of your interrogators and your guard, the sense of complete

isolation, if you know that you are not forgotten outside and that there is

a movement – this makes all the difference."

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in

the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New

York and the Netherlands. Follow her at @radicalstates.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment