Islamist

Attacks on Holidays

by Noah Beck

Special to IPT News

April 20, 2017

|

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the

first of your friends to like this. Be the

first of your friends to like this.

Nearly 50 people

were murdered on Palm Sunday when Islamic State terrorists bombed two Coptic churches in

an Easter celebration-nightmare. The next day, on the eve of the Jewish

holiday of Passover, the Islamic State's Sinai affiliate launched rockets at Israel. Nearly 50 people

were murdered on Palm Sunday when Islamic State terrorists bombed two Coptic churches in

an Easter celebration-nightmare. The next day, on the eve of the Jewish

holiday of Passover, the Islamic State's Sinai affiliate launched rockets at Israel.

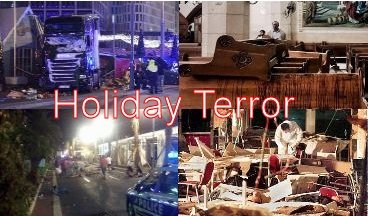

Just before Christmas, a terrorist claimed by the Islamic State rammed a truck into Berlin's crowded Christmas market,

killing 12 people. And in Australia, a group of self-radicalized Islamists planned to attack St Paul's Cathedral. In

2011, Nigerian Islamists murdered nearly 40 Catholic worshipers in a Christmas

Day attack.

Terrorists attack where and when they can. But they seem keenly aware

that turning holidays into horror can carry greater shock and terror. In 2002,

30 Israeli civilians were massacred and 140 injured by

a Hamas

suicide bomber who blew himself up as they sat for the seder,

the traditional Passover meal, at the Park Hotel in Netanya.

It isn't just terrorists who see advantages in striking during holidays.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War may be the most famous example, when the armies of

two Muslim-majority states, Egypt and Syria, attacked Israel on the most

sacred day of the Jewish calendar. That war produced an estimated 20,000

deaths.

Christians and Jews aren't the only religious groups that have been

targeted by Islamists during non-Muslim holy days. The Hindu festival of

Diwali has also been attacked. In 2005, a series of bombs killed over 60 people and injured

hundreds in Delhi; a Pakistan-based Islamist terrorist group, the Islamic

Revolutionary Front, claimed responsibility. Last October, Indian police

arrested an Islamist cell inspired by the Islamic State for planning an attack during Diwali.

Muslims are also victimized by Islamist attacks in increasing volume. A

2015 mosque bombing in Yemen killed 29 people during prayers for the Muslim holiday

of Eid. Last July, also during Eid, three people were killed at a

Bangladesh checkpoint when gunmen carrying bombs tried to attack the country's

largest Eid gathering, which attracted an estimated 300,000 worshippers.

Last May, as the Muslim holy month of Ramadan approached, a spokesman

for the Islamic State urged jihadists to "make it, with

God's permission, a month of pain for infidels everywhere." Days

later, as Ramadan celebrations stretched past midnight in central Baghdad,

a minivan packed with explosives blew up and killed at least 143 people.

Terrorists also target secular holidays. Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel, a

Tunisian resident of France, killed

85 people and injured hundreds more in a truck-ramming terrorist attack

as people gathered for a Bastille Day celebration. In New York last fall,

dump trumps were deployed to protect the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade,

after the Islamic State called it an "excellent target."

Holidays are often chosen because they are "optimal attack

days," in terms of gathering large crowds into soft targets like

houses of worship, religious markets, ceremonial gatherings, and parades.

Last November, U.S. officials warned that the coming holiday season

could mean "opportunities for violent extremists" to attack.

A terrorist attack on a holiday is also more likely to attract media

attention. And because holidays draw tourists, well-timed attacks can amplify

the economic damage that would be wrought by terror even on a

non-holiday. After a spate of attacks toward the end of 2015, "about

10% of American travelers have canceled a trip ... eliminating a potential

$8.2 billion in travel spending," reported MarketWatch.

But ISIS, al-Qaida and other Islamist terrorist groups believe they are waging

a holy war above all else. Attacking infidels, be they Christians, Jews or

Muslims of other sects, motivates jihadis more than anything else.

"Those who targeted churches on holiday celebrations tend to be

professional terrorist groups," Raymond Ibrahim, author of Crucified Again: Exposing Islam's New War on Christians,

told the IPT. By contrast, "mob attacks happen either on a Friday,

after an especially potent sermon, or whenever infidels need to be put in

their place (e.g., a Christian accused of blasphemy, then the church in his

village gets torched)."

In 2015, Islamic State warnings of future attacks against Christians noted

that Christians were their "favorite prey" and no longer

protected as "dhimmis," a reference to non-Muslims in Islam who

may, in exchange for paying the jizya tax, receive some state protection.

Thus, within the larger context of a holy war, attacks on non-Muslim

holy days can be viewed as part of the more general Islamist strategy of

humiliation, forced submission to Islam, and the denial of any competing

religion. Attacking on Diwali or Christmas or Yom Kippur is essentially

declaring that such "infidel" holy days ought to be desecrated

rather than respected. The symbolic message is akin to the one communicated

by the two Islamists who entered a French cathedral and beheaded an octogenarian priest, Jacques Hamel, during

mass services last July.

Attacking places of worship on holy days – when they are most used by

and relevant to their congregations – is also a good way to undermine these

religious institutions and their supporters. If Islamist terror makes

churches the most vulnerable on the days when they are most crowded, how

will those houses of worship attract enough followers to sustain

themselves? And how will their congregants practice their faith? The Coptic

Pope curbed some Easter celebrations in Egypt after the

recent Palm Sunday blasts.

Such questions may help to explain why Christians, who have lived in the

Middle East – the birthplace of Christianity – for millennia now constitute

only about 3 percent of the region's population, down from 20 percent a century ago.

Indeed, the only non-Muslim country in the entire Middle East is also

the safest place for non-Muslims in the region, including Christians,

Druze, and Bahai. "Christians and other minorities in Israel prosper

and grow," says Shadi Khalloul, founder of the Israeli Aramaic

Movement. "[W]hile in other countries in the Middle East, as well as

in the Palestinian Authority, they suffer heavily from the Islamic movement

and persecution – until forced to disappear."

Noah Beck is the author of The

Last Israelis, an apocalyptic novel about Iranian nukes and other

geopolitical issues in the Middle East.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment