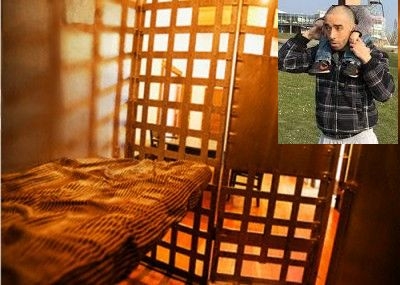

Karim

Cheurfi: From the Cauldron of Prison to the Streets of Paris

by Patrick Dunleavy

IPT News

April 24, 2017

|

|

|

|

Share:

|

Be the

first of your friends to like this. Be the

first of your friends to like this.

The initial reports

regarding Islamic terrorist Karim Cheurfi, the man responsible for the

latest attack that killed French police officer Xavier Jugele and wounded several others, contained the all-too-familiar phrase – "known to

authorities." The initial reports

regarding Islamic terrorist Karim Cheurfi, the man responsible for the

latest attack that killed French police officer Xavier Jugele and wounded several others, contained the all-too-familiar phrase – "known to

authorities."

What actually was known? Cheurfi had a predisposition for violence,

animosity toward authority – he had tried to kill police officers twice

before – and a sense of alienation. They also knew that he had spent a

significant period of his life in a place that some authorities called a radicalizing cauldron, the French prison

system. Inside those prisons, a small group of Islamic terrorists was

effectively radicalizing other inmates who came in as petty criminals with

no religious leanings, said Pascal Mailhos, past director of France's

domestic intelligence agency.

Mailhos' warning proved prophetic as French prisons spawned terrorists

like Mohammed Merah, who in 2012 murdered police officers and Jewish school children in

Toulouse, and Amedy Coulibaly, who killed a police trainee before

storming the Hyper Cacher kosher supermarket and killing four hostages. Charlie

Hebdo attacker Said Kouachi, like Karim Cheurfi, came out of the joint radicalized and ready to kill law enforcement, military

personnel and innocent civilians in the name of Allah.

This problem is not unique to France. Former inmates who turned to the

violent path of jihad plotted or carried out terrorist attacks in the United States, Belgium, Canada,

Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom.

For some, particularly for those who have spent time in prison, the

radicalization process from conversion to violence is more accelerated.

"Some individuals, particularly those who convert in prison, may be

attracted directly to jihadi violence...for this group, jihad represents a

convenient outlet for (their) aggressive behavior," the Central

Intelligence Agency said in a report, "Homegrown Jihad – Pathway to

Terrorism."

When you combine the ingredients of violent aggressive behavior,

animosity toward authority, incarceration, and radical Islamic ideology,

you will almost certainly produce a deadly toxin. French prosecutor

Francois Molins insisted that Cheurfi showed no signs of radicalization

prior to the attack. Missing the signs could be the result of bad eyesight

or, a lack of training. "We don't have anyone trained for

anti-radicalization," said David Dulondel, the head of the union representing

officers at France's Fleury-Merogis maximum security prison. "We can't

say whether someone is in the process of radicalizing or not."

Despite an acknowledged problem with insufficient training, groups like

the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) seek to censor any mention

of Islamic radicalization from American law enforcement and military training.

In 2004, the FBI's official definition of radicalization was "the

process of attracting and possibly converting inmates to radical

Islam." They since have been pressured to change the term to

"violent extremism."

Removing warning labels from canisters containing caustic material does

not render the substance inside harmless. It only increases the risk of a

deadly incident. Toxic waste spills are often the result of carelessness.

Prison radicalization should not be treated this way. We must put the

tools in place to monitor and control this threat. Others have done it.

Following last month's Westminster Bridge attack by Khalid Masood, British authorities announced the

formation of a task force that will combine intelligence, law

enforcement, corrections and probation personnel to look at literature,

clergy, and other influences available in prisons. The task force will also

closely monitor recently released inmates for changes in behavior or

association with known radical mosques or people. France, which has suffered

its share of jihadi violence carried out by ex-inmates, had to admit that its program to address prison

radicalization had been an utter failure. Yet it has not made any

significant changes.

Here in the United States, it is imperative that the Justice Department

and the FBI revise the Correctional Intelligence Initiative Program to include

the proper vetting of clergy and a post release component to track people

who were radicalized or previously incarcerated for terrorist crimes. The

initiative started in 2003 with a mission to "detect, deter, and

disrupt efforts by terrorist and extremist groups to radicalize or recruit

within all federal, state, territorial, tribal and local prison

populations."

Failure to effectively address the ongoing threat is not an acceptable

option. At some point there will be a price to pay.

IPT Senior Fellow Patrick Dunleavy is the former Deputy Inspector

General for New York State Department of Corrections and author of The Fertile Soil of Jihad. He currently

teaches a class on terrorism for the United States Military Special

Operations School.

Related Topics: Patrick

Dunleavy, Champs

Elysees attack, Xavier

Jugele, prison

radicalization, Karim

Cheurfi, Pascal

Mailhos, Homegrown

Jihad – Pathway to Terrorism, David

Dulondel, Francois

Molins, CAIR,

Correctional

Intelligence Initiative

|

No comments:

Post a Comment